The politics of the military recruitment crisis

Using military data and recent research on the experience of young recruits, we outline entrenched problems faced by service personnel and current opportunities for change which must not be overshadowed by operational and political demands for more recruits – or even national service.

Summary

Fuelled by war-footing narratives, the long-standing recruitment shortfall in the armed forces has developed into a ‘recruitment crisis’ in the media. Changing attitudes of young people towards enlistment, and conscription, often get blame for the failure of the military to meet recruiting targets. However, the figures show that large number of applications to join up continue to be made but, for various reasons, these have not translated into new recruits. This suggests that, in constantly pushing for more recruits, the armed forces are actually demanding more suitable recruits, rejecting in one way or another the majority of those that do apply.

Ministry of Defence statistics show that the high net outflow of the last few years – which has caused such alarm – is now decreasing. It is likely to be partly a consequence of the high net intake in the previous period, which was a response to very prominent recruitment marketing in the years leading up to and during the Covid pandemic. A peak in the number of personnel who left before they finished training also suggests that many were persuaded to join but then soon found military life was not for them.

The loss and set-back for would-be recruits who do not make it through the application process or who leave the forces without completing their training is not given due weight in calls for more impactful recruitment initiatives. For the one quarter to one third of recruits who become ‘early service leavers’, research shows that there are significant associated difficulties. There are also high levels of dissatisfaction and low morale, and considerable experience of discrimination and abuse that result in significant harm. With the average length of a career in the armed forces less than 10 years, and many serving only a few years, the crisis is more one of retention.

Recruitment marketing and the political rhetoric around it – emphasising self development and social mobility – presents military life in unrealistic ways and masks the reality and risks of joining up. Recent research by the Child Rights International Network provides powerful insight into how the youngest recruits – aged 16 and 17 – are most affected by these negative outcomes.

While the independent Haythornthwaite Report on ‘incentivisation’ of recruitment and retention published in 2023 is perceptive in some areas – such as the problem of the military’s exceptionalism – its recommendations for drawing in skilled young people raise familiar concerns. Increasing the targeting of young people in all areas of their lives – in schools and colleges and youth activities, in public space and online spaces of social media and gaming – does not address the question of whether their consent to join the forces is fully informed, with awareness of all the risks and obligations involved. New understanding of moral risk and moral wrongs in the armed forces, developed by academics Jonathan Parry and Christina Easton, argues that the moral burden of military involvement is outsourced from the institution to the individual. This has implications for current armed forces recruitment practices.

The current Defence Committee inquiry on the experience of women in the armed forces must address the negative experiences of many of the youngest women – but also very young men – in the army, and new calls for conscription or national service must not put operational and political demands above their well-being.

Coming up

- The new ‘recruitment crisis’

- What’s behind the high net outflow?

- Applications are high so why is intake so low?

- The crisis in retention

- Dissatisfaction and low morale

- Everyday abuse and discrimination

- ‘Assimilation rather than integration’ – leveraging exceptionalism

- Recruitment rhetoric – offering social mobility or a risky environment and unrealised hopes?

- More of the same ‘solutions’

- New calls for national service

- The ethics gap and moral risk

- Conclusion: operational and political demands are not enough

The new ‘recruitment crisis’

Military recruitment in the UK has become a hot topic again. Last year, concerns about historic low levels of armed forces personnel were expressed across parliament and the media, as MoD statistics showed a high net outflow of personnel and failure to meet recruiting targets across the services. More recently recruitment shortfalls have featured as part of the broader debate about how the UK and Europe should reconfigure defence in the wake of withdrawal of support by the US. Calls for the reintroduction of conscription – phased out in the early 1960s as the UK moved towards an all-volunteer force – have resurfaced.

Reference to clichés and disparaging tropes about the lack of resilience or patriotism of the Gen Z generation, fail to understand why there is a reluctance to consider a military career amongst young people.

Alarm about recruitment shortfalls is not new however, as we discussed in our Selling the Military report (page 10). Debate is heightened around, or as a result of, periods of conflict such as the invasion of Iraq and often conducted in the media and with a tone of operational but also moral panic. Reference to clichés and disparaging tropes about the lack of resilience or patriotism of the Gen Z generation, fail to understand why there is a reluctance to consider a military career amongst young people.

Polls and opinions about attitudes to military service do indicate that many young people are unwilling to enlist, but this is hardly surprising. The impact of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan still resonate. And, apart from how attitudes to recruitment and conscription are affected by long-term social shifts, years of coverage about toxic military culture and the difficulties that veterans face – not to mention the daily atrocities streamed from current war zones – provide plenty of rational reasons for widespread critical perspectives about military action.

But, as we discuss here, the ‘crisis’ is significantly not about the choices of young people. Looking at the statistics, it is clear that there are still plenty who put themselves forward for joining up, yet the military fails to sign the vast majority of them up. Some of this is about failing processes but it also suggests that, in constantly pushing for more new recruits, the armed forces are actually demanding more suitable recruits, rejecting in one way or another the majority of those that do apply. Failure to meet the very particular demands of the military is expressed as a failing in a whole generation of young people.

Military marketing and wider promotion plays a significant role in generating significant levels of initial interest, feeding on self-development and social mobility narratives. If there is a crisis, it is because the armed forces have failed to deliver on the promise of these marketing messages – the armed forces as somewhere where everyone is welcome, where everyone can find their place and develop. Retention rates are poor as those that do enlist often leave early or have short careers, and face a range of difficulties and risks that are associated with military life.

The youngest and most vulnerable recruits are at the highest risk from the challenges of military culture. As with other negative impacts on individuals who have served in the armed forces, these costs are rarely taken into consideration in the politics of recruitment.

What’s behind the high net outflow?

Ministry of Defence statistics show a post-pandemic failure to meet recruitment targets and a high net outflow of personnel across the armed forces. Net outflow means that there are more people leaving the armed forces than joining. The Guardian reported in early 2024:

‘Army and navy recruitment targets have been missed every year since 2010…Royal Navy personnel numbers are 5% below the target set in 2015, and RAF numbers are 9% below target, while the army is only ahead because its target was cut to 73,000 in 2021.’

Its long been clear that the performance of Capita – the private company that won the army recruiting contract in 2012 – has been one part of the problem, as Parliament’s Defence Committee explored again last year. However, the figures show that the intake of recruits to the navy and RAF have also declined, so there are more general problems with recruitment systems. This is evidenced by the low conversion rate of applications to recruits, which we explore below.

The Guardian noted that the net outflow of full-time regular service personnel in the year to September 2023 was 5,790 across the armed forces and, as with similar reporting last year, that the army was the smallest size it has been for three centuries. Some of this is due to the planned decline in the strength of armed forces from 2010 to 2014 which resulted in nearly 20% reduction in the number of regular personnel.

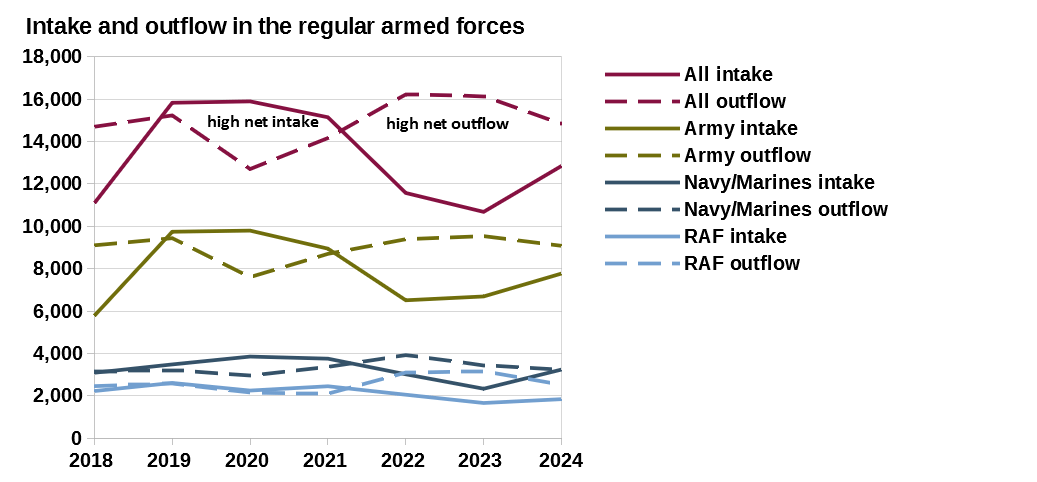

Focusing on what figures for a single year show is generally less instructive than looking at trends over a period, as there is considerable variation in annual intake and outflow. While 2023 did see a high net outflow across the services, just one year later in September 2024, the net outflow had more than halved to 2,628. See Figure 1 below. The latest figures show a further reduced net outflow of less than 2,000 in the year to December 2024 (table 4).

Figure 1 shows the intake and outflow for the three services and the armed forces as a whole over a seven year period. The high net outflow of the last few years is shown by the large difference between outflow and intake numbers. This difference is now decreasing for all three services. Source: Tables 5a and 5c, Quarterly service personnel statistics: 1 January 2025, MoD 2025.

Figure 1 also shows that between 2019-21 there was a significant net intake, as a relatively high number of people joined the armed forces in those years. This coincides with the Covid period which the armed forces utilised to appeal to potential recruits. It also reflects the high profile of armed forces marketing in the years running up to 2020, particularly the army’s ‘This is Belonging’ campaign which started in 2017 and resulted in large increases in the number of applications to join up.

This high intake to high outflow shift could indicate that many who joined because of Covid or persuasive marketing realised after enlisting that a military career was not for them after all.

After these few years of high intake, there was then an increase in personnel leaving, resulting in the recent years of high outflow. While the net outflow has been larger for the army, it has also been proportionally significant for the navy and RAF, but scaled down as they are smaller forces.

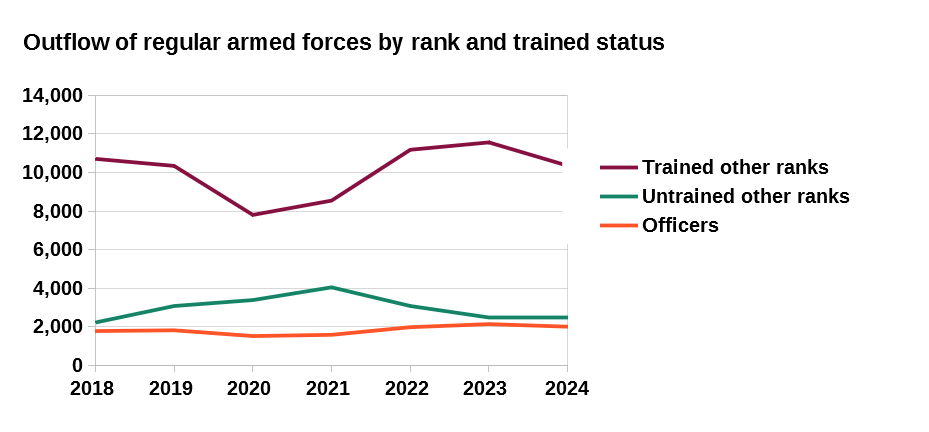

This high intake to high outflow shift could indicate that many who joined because of Covid or persuasive marketing realised after enlisting that a military career was not for them after all. This is also suggested by the outflow figures for recruits who left before they finished training, which was high in the period from 2020 to 2022. See Figure 2.

The number of untrained personnel leaving peaked in 2021 when one third (34%) of all ‘early service leavers’ from the regular other ranks (non-officers) left before finishing their training. This is much higher than the periods before and after such as in 2024 when only one fifth (19%) of personnel leaving were untrained.

These statistics do not show how many of those who enlist end up leaving as ‘untrained’ as this requires cohort data which tracks the status of each recruit over time. Child Rights International Network (CRIN) obtained cohort data for army recruits for a four year period from 2017/18 to 2020/21; this data shows an average of one quarter (27%) of recruits to the other ranks had left before they were fully trained.

Figure 2 shows how many officers and trained and untrained other ranks (non-officers) left the armed forces over a seven year period. While the number of officers leaving remained stable, there was more fluctuation for other ranks. In particular, there was an significant increase in other ranks leaving before finishing training, peaking in 2021, which has now reduced to previous levels. Source: Table 5c, Quarterly service personnel statistics: 1 January 2025, MoD 2025.

Applications are high so why is intake so low?

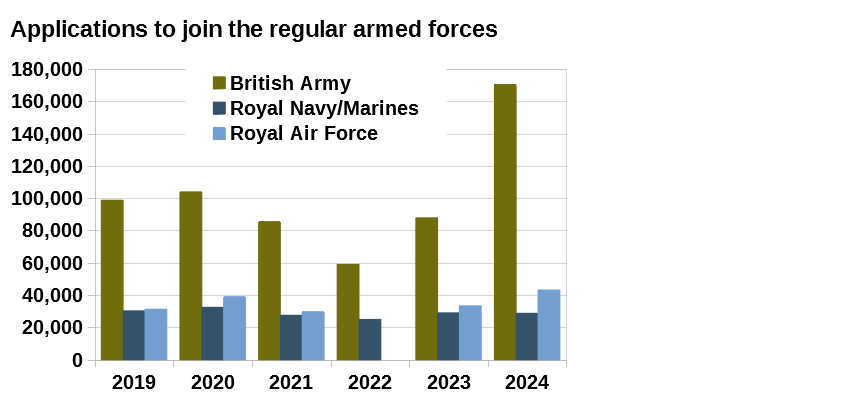

Application figures are harder to interpret than intake and outflow because how an application is defined and recorded has changed over time and differs between the services. There have also been large-scale losses of applications due to system failures which in themselves have added to reduced intake. The National Audit Office identified technical issues relating to a new online application process as a significant factor in recruitment shortfall in 2017. And during 2021 to 2022, there was a loss of many thousands of applications which affected intake in the subsequent period.

In 2024 it was reported that fewer than one in ten applications during the previous year had resulted in an enlistment, with over half (74,000 out of 137,000) not proceeding because of the length of the process.

Without reading too much into smaller year on year differences, the figures do indicate that plenty of people are still applying to join the armed forces (tables 9a-9c). In 2024 the number of applications for the army and RAF were considerably higher than in 2023. See Figure 3. This is likely to reflect various societal factors, such as the ramping up of the war-footing narrative since the invasion of Ukraine, the cost of living crisis and wider economic issues.

Figure 3 shows the number of applications to join the regular (full-time) armed forces over a six year period, in the 12 months to September each year. Army applications for 2021-22 reflect a loss of 10,000-15,000 applications due to technical reasons. See table notes for definition difference across the forces and years, and for gaps in the data. Source: Table 9a-9c, Quarterly service personnel statistics: 1 January 2025, MoD 2025.

Even before the most recent increase in interest for the army and RAF, the number of applications is many times higher than the number of enlistments. So why don’t more of these applications translate into new recruits? In 2024 it was reported that fewer than one in ten applications during the previous year had resulted in an enlistment, with over half (74,000 out of 137,000) not proceeding because of the length of the process. The army had the worst conversion rate of applicants to recruits although its average time from application to enlistment was the shortest at eight months. The average for the Royal Navy/Royal Marines and RAF were 9 and 10 months respectively. The Telegraph calculated the accumulated affect over a decade:

‘While just over one million people applied to join either the Royal Air Force (RAF), Navy or Army since 2014, three in four gave up on the process of joining, resulting in the Ministry of Defence (MoD) signing up just over 132,000 people and rejecting almost 170,000.’

Taking over from Capita, another huge outsourcing company, Serco, has now been awarded the new contract for all armed forces recruitment from 2027, after three years delay. Only time will tell if this fully privatised system will do any better, although it is the armed forces that set the regulations for joining. The government has promised that the new tri-service recruiting system will revolutionise the waiting times for applicants from 2027. Last year, the army lifted a ban on soldiers having beards and 100 other regulations relating to fitness requirements and minor illness after Capita complained that the army’s screening process rejected many on the basis of certain physical and mental health conditions, and visible tattoos. Not only have these traditionally strict criteria not been communicated adequately to applicants at an early stage, but marketing which emphasises equality of opportunity gives the impression that all would be welcome when this is clearly not the case.

The crisis in retention

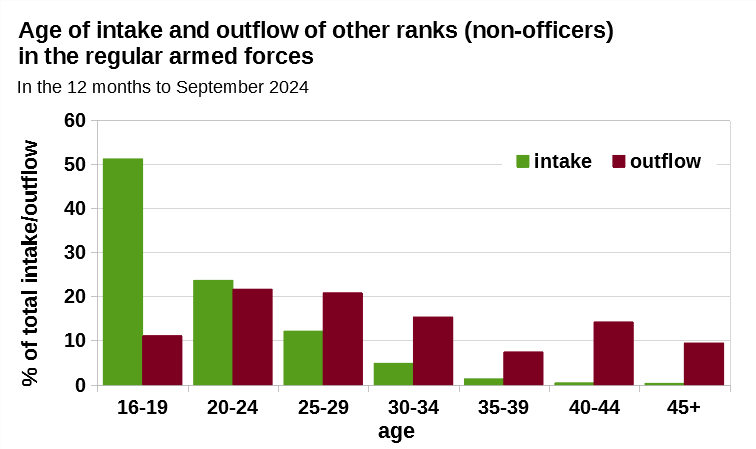

Overall, most recruits to the armed forces are very young, with over half last year aged 16 to 19. See Figure 4. This perhaps reflects the age of those most susceptible to recruitment advertising but it also varies between the forces. There are more recruits to the army age 16 than any other age (table 9a). In the year to September 2024, they comprised 15% of all regular (full-time) intake to the army, with 17 year-olds making up another 12%. The navy and RAF recruit far fewer under-18s and very few 16 year-olds. Their recruits are more likely to be 18 or 19 years old.

While the high net outflow of the last few years is decreasing (Figure 1), the number leaving the armed forces remains high. The most recent figures show reducing outflow since 2023 but about 15,000 people left in 2024 (table 5c).

As we discussed above, the data strongly suggests that one reason that people leave is the early realisation that military life is not for them, about one fifth before they have even finished training (Figure 2).

Figure 4 shows that, in the year to September 2024, personnel aged 16-19 and 20-24 accounted for 11% and 22% of all outflow from the regular armed forces. For army personnel who leave, 38% are in these young age groups. Data by age group does not show whether personnel were trained or untrained when they left but it is likely that many of these, and most in the 16-19 age group, will not have completed training.

CRIN’s analysis of cohort data for the army, which tracks the status of individuals over time, shows that a quarter (25%) who join as adults leave before they finish training. This compares to one third (33%) who joined at 16 or 17 years old who leave before they finish training.

Figure 4 shows the percentage of people entering and leaving the regular (full-time) armed forces for each age group, in the year to September 2024. By far the largest intake is of 16-19 year-olds. The largest outflow is of 20-24 year-olds. Source: tables 9 and 13, UK armed forces biannual diversity statistics: October 2024, MoD 2025.

Looking at those who leave once they are trained, the statistics show an annual outflow rate of nearly 10% (table 5e). More than half of this is ‘voluntary outflow’ with the rest accounted for by people reaching the end of their military careers or leaving due to reasons ‘unspecified, disciplinary, medically discharged and unsuitable’. In numbers, of the 12,165 who left the armed forces last year, 7,511 chose to do so before the end of their contracted period (table 5d). As is to be expected, slightly higher voluntary outflow rates are recorded for other ranks than officers. The RAF have the lowest voluntary outflow rates.

An independent inquiry on ‘incentivising’ recruitment and retention was commissioned by the Secretary of State for Defence and published in 2024. The Haythornthwaite Review reported that the median length of service in the army and navy was only 9.5 years, although longer in the RAF at 12.5 years. Half (50%) of personnel have served less than eight years and 60% are under the age of 35. A young workforce with a high turnover reflects that, in line with changing work patterns across society, the military is not a career for life and many are only in it a short time.

Dissatisfaction and low morale

Changing expectations about careers and fulfilment vis-a-vis life in military institutions is also captured In the Armed Forces Continuous Attitudes Survey, which shows overall satisfaction with Service life in 2024 at only 40%. This has been declining since a high of 61% in 2009. Morale was assessed as ‘low’ by 58% of service personnel across the armed forces. There is fluctuation across services, ranks and years but a general picture emerges of a significant degree of dissatisfaction across many areas. The most cited reasons for leaving the armed forces are the impact of service life on family and personal life, followed by the availability of opportunities outside of the military, childcare challenges, low job satisfaction levels and local morale. Less than half of personnel in 2024 would recommend joining to others (47%) or feel strongly attached to their unit (47%). ‘Belonging’ is not working for many.

Since coming into office, the Labour government have responded to the crisis with a series of announcements for retention payments, the above-inflation salary increase awarded to many public sector workers, and also a large increase in the salaries of new recruits. There have also been other commitments in relation to childcare and accommodation and legislation to install an Armed Forces Commissioner.

Everyday abuse and discrimination

Sexual abuse and harassment against women, but also against men (particularly as new recruits), in military institutions is still widely reported. Thousands of women came forward to give evidence to a parliamentary inquiry in 2021, which resulted in significant media coverage and parliamentary discussion. The anecdotal evidence suggests a clear impact on retention. The armed forces first conducted sexual harassment surveys nearly 20 years ago, and there have been a number of reviews and reports, including the 2019 Wigston report on Inappropriate Behaviours, established in the wake of a prominently reported case of a 17 year old attacked in her bed by six soldiers. Yet, the military has continually been on the back foot in terms of putting reforms in place, which they have approached in a reluctant and piecemeal fashion – such as the new serious complaints unit and taskforce to counter violence against women and girls recently announced in response to the suicide and inquest of 19-year-old army gunner Jaysley Beck.

Racism has had less exposure but, along with women, Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic personnel are over represented in the service complaints system, although no reporting from the Ombudsman has been available since 2022. In one high-profile case, Kerry-Ann Knight, the black poster girl for a British army recruitment campaign focused on diversity, took the military to court and won damages after enduring racial abuse over her decade-long career. She says she had to serve alongside soldiers who claimed to support far-right groups.

In follow-up work to the 2021 report on Women in the Armed Forces, Parliament’s Defence Committee has been gathering more evidence of the everyday experience of women and the impact of any improvements implemented by the military. Written evidence suggests there is still a long way to go.

The new inquiry seems to be paying more attention to how sexism and racism, and other abusive behaviours, affect the youngest recruits aged 16 and 17, although oral evidence sessions have yet to hear from anyone other than senior military figures, who seem to display less than sufficient grasp of the issues. Both the family of Jaysley Beck and Kerry-Ann Knight, among many to be represented by the Centre of Military Justice, experienced inappropriate behaviour at the Army Foundation College in Harrogate. Beck was 16 years old when she joined the army and, before she left there aged 17, was in a relationship with a instructor some years her senior. It is a criminal offence for an adult to have sexual contact with a person under the age of 18 when they are in a position of trust. The service inquiry into Jaysley’s death found that this breach occurred ‘in spite of…the safeguarding culture at the college’ (page 40).

Kerry-Ann Knight’s experienced racial and sexual harassment herself as an instructor at Harrogate and her witness statement cited multiple examples of serious maltreatment of recruits, including physical and sexual abuse. Both cases form part of a list of a decade of physical, sexual and emotional abuse at Harrogate presented by CRIN as evidence to the inquiry. The list covers multiple instances of criminal behaviour relating to physical and sexual abuse involving scores of victims (also documented here). The army’s own research found that nearly half of girls at Harrogate experienced bullying, harassment or discrimination in 2020.

Kerry-Ann Knight’s experienced racial and sexual harassment herself as an instructor at Harrogate and her witness statement cited multiple examples of serious maltreatment of recruits, including physical and sexual abuse. Both cases form part of a list of a decade of physical, sexual and emotional abuse at Harrogate presented by CRIN as evidence to the inquiry. The list covers multiple instances of criminal behaviour relating to physical and sexual abuse involving scores of victims (also documented here). The army’s own research found that nearly half of girls at Harrogate experienced bullying, harassment or discrimination in 2020.

Retired Lieutenant colonel Diane Allen – in influential voice for women seeking change in the armed forces – is one of a number whose evidence describes military sexual trauma and the compounding impact of ineffective or dismissive action by the chain of command as well as the lack of progress at senior levels in providing substantive remedies. Alarmingly, she describes how hostility towards women has grown in some parts of the military in response to calls for change (page 4) and how ‘toxic pockets’ should be ‘declared…unsafe for minority individuals’. Referencing ‘the RAF Red Arrows, the RN submariners, the Army’s Larkhill site, and Harrogate training establishment’, she says that:

‘We must stop sending vulnerable individuals to be groomed and targeted, where leadership is too weak to control the “laddish culture”.'(page 7)

Another veteran giving written evidence has highlighted that ‘misogyny, inappropriate sexual behaviour, anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment and racism’ are not just held by older people in the armed forces. She had dealt with these offences involving recruits aged 16-22, and concludes that ‘these issues are not age related’. While this reflects trends in civil society, such as incel culture and the growth of the far-right, the nature of military institutions could aggravate their impact.

CRIN’s report on suicide of 16 and 17 year-olds in the armed forces provides heartbreaking testimony and data to show that early enlistment is associated with an increased risk of suicide. Pre-military vulnerabilities – including childhood adversity and vulnerability to stress linked to adolescent brain development – as well as stresses related to training and bullying, and post-military factors – particularly for young and/or socio-economically disadvantaged – all play a role.

‘Assimilation rather than integration’ – leveraging exceptionalism

Recognising the importance of embracing the diversity of society – not least for fulfilling recruitment targets – equality and inclusion are a prominent element of recruitment efforts by the army, navy and RAF, much to the ire of the Daily Mail and Tory ex-defence ministers. The military puts significant emphasis on attracting (or ‘seducing’) women and ethnic minorities to its ranks. Yet, this endeavour is clearly still at odds with traditional military culture that privileges white men within rigid hierarchies. This culture remains entrenched, as described by the Wigston report which did pay attention to the chain of command in replicating a discriminatory culture:

‘Many victim support groups consider the Armed Forces’ culture exacerbates the opportunity for inappropriate behaviours to occur. They consider instances are commonplace, with conscious and sub-conscious behaviour, microaggression, psychological bullying and intimidation, including through social media and on-line behaviours, taking place at all levels, with junior ranks, women and BAME personnel the most likely victims of this behaviour.’ (page 10)

The Hayforththwaite Review, an assessment from outside of the military, reported:

‘Today, the Armed Forces too often expect people to assimilate into their old culture, rather than going some way to adapt to the society they defend.’

The author states that while ‘the traditional pool of recruits that [this culture] attracts is shrinking’,

‘The exceptionalism of the Armed Forces, in the sense of being apart from civilian society, creates a degree of insulation that allows civilian society and the Armed Forces to follow divergent paths in their understanding of what is desirable in terms of behaviours. This is exacerbated by the expectations of assimilation in which those who disagree with the status quo will find it more difficult to stay long enough to be in a position to facilitate change.’

While relatively honest in this evaluation, this review – and others – fail to consider how the inherent violence of the military – in what it asks people to do, and how it reshapes them to do it – might play a part.

While relatively honest in this evaluation, this review – and others – fail to consider how the inherent violence of the military – in what it asks people to do, and how it reshapes them to do it – might play a part.

Recruitment marketing has long bought into the military’s exceptionalism. The sense that only in the armed forces can one ‘be the best’ was first introduced by the army in 1994). This has intersected with ideas around the military as a special place where you can find yourself and belong to your group, and where equality of opportunity is available. This sets up an opposition to civilian life. These strains are evident in the main marketing campaigns of the last decade – Made in the Royal Navy, the army’s This is Belonging and the RAF’s No Ordinary Job.

Despite these narratives running counter to much of the lived experience, commentators have often criticised equality-focused advertising as too ‘politically correct’, suggesting an active support for the military’s exceptionalism. As Trump’s administration has brought about a rapid shift in US military recruitment messaging towards more macho themes, as part of a widespread reversal of diversity, equality and inclusivity policy in the US, some UK commentators have been quick to argue that recruitment here should also be unleashed from ‘messing around with things that seem to be not relevant to its core purpose’.

Recruitment rhetoric – offering social mobility or a risky environment and unrealised hopes?

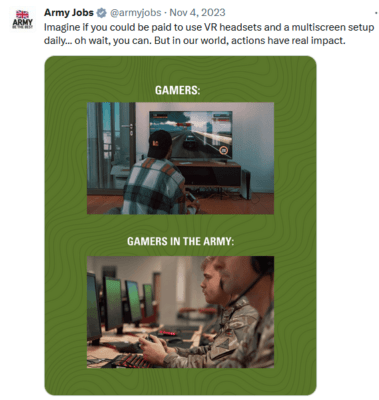

The armed forces will have spent over £50 million on marketing in the 2024-25 financial year, with the British Army nearly doubling its spend from the previous year. The scale of resources behind recruitment marketing allows it to target different audiences across multiple channels and platforms, with increasing stratification and sophistication. The armed forces have a presence on all social and traditional media and utilise every opportunities to gain access to young people – in the education system and youth activities, in public spaces, and more recently on gaming platforms and esports spaces, as we report on here.

At the Labour party conference last year, the UK Defence Secretary John Healey called on gamers and coders for a new fast-track recruitment route to the armed forces for cyber specialists, in a significant new direction for recruitment processes. Whether gamers will heed this ‘your country needs you’ call is debateable, given the clash – as Haythornthwaite expresses it – between institutional ‘rules and process’ that makes people feel disempowered by the system and expectations ‘shaped by a world that is changing with unprecedented pace’ (page 1).

At the Labour party conference last year, the UK Defence Secretary John Healey called on gamers and coders for a new fast-track recruitment route to the armed forces for cyber specialists, in a significant new direction for recruitment processes. Whether gamers will heed this ‘your country needs you’ call is debateable, given the clash – as Haythornthwaite expresses it – between institutional ‘rules and process’ that makes people feel disempowered by the system and expectations ‘shaped by a world that is changing with unprecedented pace’ (page 1).

Reflecting the demand for skills and ‘pace’, the services’ websites are an overload of slick still and moving images, slogans and statements with ‘role-finders’ to progress young people’s dreams, promising multiple opportunities for developing specialisms even for 16 year-olds with no qualifications.

Perhaps the most consistent theme of recruitment marketing is that a military career brings self-development and long-term personal fulfilment. As we’ve discussed before (page 29) using the frame of individual fulfilment in the context of conflict – elsewhere in the world – depoliticises military action by focusing on the experience of individuals in the armed forces. The most recent ‘You belong here’ adverts from the army mix a ‘what’s in it for me’ theme with various action and crisis scenarios. In a shift away from explicitly centring diversity, it is instead depicted through some of the lead characters. There is more focus on combat; recent TV adverts boldly state that ‘a soldier turns an army into a modern fighting force’, and ample footage of ‘war-fighting’ scenarios is available on the army’s YouTube channel.

The RAF also emphasises the intersection between military power and personal development with its current ‘find your force’ theme. With a nod to Star Wars, its claim to be ‘the force protecting space’ is a stretch too far even in the world of less-than-realistic recruitment adverts. The Royal Navy and Royal Marines emphasise ‘adventure, reward, growth’ within the context of ‘making a difference’ (navy) and going ‘to your absolute limit’ (marines).

This self development narrative is echoed in political rhetoric, which asserts that the military is a route to social mobility. A 2024 parliamentary report on ‘readiness for war’ stated – without evidence – that the armed forces have ‘been a driver of social mobility throughout history, and it is our responsibility to build on the opportunities offered to help people achieve their potential’. And in a recent debate in the House of Lords, the Labour Minister of State for the MoD referred not only to opportunities for the 16 and 17 year old recruits at the army’s training establishment in Harrogate that would ‘not be available to many’, but also that many there ‘are from the most difficult circumstances’. This says more about how the armed forces target their recruitment than about how young people actually benefit, as CRIN discussed in their Conscription by Poverty report.

The Army Foundation College in Harrogate is a training establishment but is often presented as more of an institution for education, or even welfare, which aims to set young people up for life. A recent defence minister stated that it ‘offers a significant foundation for emotional, physical and educational development throughout an individual’s career’.

Some claims about social mobility in the armed forces utilise individual and anecdotal success stories to try to make the point. While it is certainly possible that some recruits from lower socio-economic backgrounds could benefit, it is not a claim that can be made without hard evidence. Yet, the MOD does not collect data on socio-economic backgrounds of personnel ‘which could inform an assessment of levels of social mobility’, as categorically stated by a defence minister in 2020. He also acknowledged that:

‘Information on the educational backgrounds of officers is also not held by the MOD, making it hard to assess (or make claims about) whether the traditionally middle and upper class commissioned ranks are more open to people from lower socio-economic backgrounds.’

Not only are the armed forces not in a position to claim to be a ‘driver of social mobility’ without having data on the socio-economic background of recruits, but there is hard evidence that, for many, entering the forces has a halting effect on their prospects.

What is the cost of these high wastage rates for the armed forces and, more importantly, for the ‘early service leavers’ who drop out untrained.

As discussed above, around one quarter of adult soldiers and one third of junior soldiers leave before they finish training. What is the cost of these high wastage rates for the armed forces and, more importantly, for the ‘early service leavers’ who drop out untrained. The price is particularly high for 16 and 17 year-olds who will have turned away from mainstream education to pursue a career in the forces. Research identifies that early service leavers face significant risks on re-entering civil society, which ‘are tied to their pre-enlistment experiences and often further exacerbated because their experience in Service is, by definition, too short to fully address those issues’.

CRIN also found that career progression for the youngest soldiers is more limited as they were ‘half as likely as adult recruits to have reached the rank of sergeant or above’. If a concern for social mobility is genuine, it would best be served by ‘encourag[ing] more young people to continue in full-time education up to age 18 to enhance their qualifications for lifelong employment, while leaving pen the option of enlisting thereafter.’ Haythornthwaite also notes that, despite increases in the recruitment of women and ethic minorities, they are poorly represented among officers and in senior ranks.

The youngest soldiers are also more at risk during their training and careers. The army is dependent on these very young recruits for ‘high-risk infantry jobs’ yet they are particularly vulnerable because of their youth, which is exacerbated by the stress factors, disadvantaged backgrounds or other childhood adversity that is common amongst this group. The army’s own unpublished research on the experience of female junior soldiers at Harrogate found that they were particularly subject to an ‘erosion of resilience’ by being there (page 28). They round that, while girls are more subject to ‘stressors of training life’, boys at Harrogate would also benefit from extra support. Academic research has shown that, compared to older recruits and comparable civilians groups, they are more subject to long term stress-related mental health problems.

More of the same ‘solutions’

The Haythornthwaite Report puts significant emphasis on overcoming skill shortages in the armed forces. While lack of skills is identified as ‘in part developed and set at the intake stage’, and a problem of the ‘base-fed model’ (page 67), the author does not discuss to what degree this demand for skills is at odds with continuing to recruit young schools leavers with few or no qualifications.

While perceptive in some areas, the report’s recommendations for drawing in skilled young people raise familiar concerns. He references the National Recognition of our Armed Forces report from 2008 which has been critiqued as part of a ‘militarisation offensive’ and bemoaned ‘a fundamental lack of understanding as to what the armed forces actually do’. Blaming a lack of visibility echoes the authors of the 2008 report, despite the huge increase in ways of reaching young people offered by the diversity of media today and the many ways in which the military has been promoted across society in the intervening years.

The call for schools and colleges, cadet forces, STEM education and esports events to be ‘exploited’ for recruitment opportunities is not only bizarre, given that no-one currently exploits them as much as the armed forces, but also lacking in any ethical judgement.

The report recommends a ‘five-step approach…to engage future generations’, going over much of the same ground that has become extremely familiar to the armed forces in the last 15 years (page 68). ‘Building understanding and interest’ is how the armed forces have long presented their recruitment activities in schools, being careful to emphasise that ‘it is not about why they should sign up’ – a too subtle distinction to mean much in practice. The military’s social media channels and more formal public communications are producing very regular news and narratives, with a considerable degree of success in influencing media debates. ‘Authentic storytelling from real Servicepeople’ is a fixture of the armed forces’ YouTube channels. Given the reputation of influencers, to suggest that they should be cultivated in order to work with the armed forces and lure young people in – without an understanding themselves of what is at stake – is alarmingly irresponsible.

Finally, the call for schools and colleges, cadet forces, STEM education and esports events to be ‘exploited’ for recruitment opportunities is not only bizarre, given that no-one currently exploits them as much as the armed forces, but also lacking in any ethical judgement. The confident statement that there will be more recruits ‘once young people genuinely understand the armed forces and the opportunities they offer’, suggests that many significant factors relating to recruitment and retention have not really been understood.

New calls for national service

As part of the moral and operational panic of this current moment, calls for the return of national service or conscription also make a regular appearance. On his way out of office in January 2024, General Sir Patrick Saunders called for British citizens to be ‘trained and equipped’ to fight in a potential war with Russia, followed by General Sir Richard Sherriff, the UK’s former senior NATO commander. Others have framed national service as a way to provide structure and purpose to young people, an opportunity to develop patriotism, as well as a solution to the recruitment crisis. The blatant attempt of the Conservatives to harness this topic in the 2024 election was met by resistance from both young voters and the armed forces.

In response to the Latvian President’s recent call for European countries to introduce conscription, the UK government has stated that it is not considering it, but warned that this could change in a ‘new reality’. While an Lib Dem MP on the parliamentary Defence Committee has since stated that there is ‘no question’ that conscription would be introduced if the UK was at war with Russia, some voices from within the armed forces continue to be cautious. Recognising that conscription would be ‘impractical and unlikely’ and that young people do not want the ‘coercion of mandatory service’, a former army colonel has argued for a voluntary ‘halfway house’ system which could involve either an expanded reserve force or a ‘national resilience force’.

In lieu of change in this area, some government ministers seem to be acting as recruitment influencers themselves. While defending cuts to benefits, including the removal of all health benefits to those under 22 years old, the Labour minister Liz Kendall recently stated that the unemployed young would be pushed towards a military career. She clearly doesn’t realise that job centres have been signposting people in the direction of the armed forces for years. The Chancellor of the Exchequer has also been talking about ‘good jobs in the armed forces’ and defence industry.

The ethics gap and moral risk

We have briefly discussed some of the ethical concerns around the recruitment of young people into the armed forces. The gap between marketing narratives and the reality of military life, exposure to physical and mental harm, the risks associated with dropping out early or leaving after only a few years, and depoliticising military action and focus instead on opportunities for self-development and fulfilment. Far from providing a route away from childhood adversity or deprivation, military service can exacerbate its effects. There is also a wealth of research of the difficulties faced by older veterans.

The armed forces are powerful institutions that have national defence agendas and recruitment targets to fulfil. That agenda differs from what is in the best interests of young people.

Fundamentally, the armed forces are powerful institutions that have national defence agendas and recruitment targets to fulfil. That agenda differs from what is in the best interests of young people. In needing to be visible to children in order to recruit personnel at a young age, the armed forces must utilise all opportunities and take advantage of the impressionable years of childhood, young people’s vulnerabilities and lack of other opportunities.

As noted above, Haythornthwaite is happy to recommend that all areas of children and young people’s lives are ‘exploited’ by the armed forces without interrogating the ethical foundation for this. Should the personnel demands of national institutions be given free rein within education and youth services – which have a different remit relating to the best interests of young people – especially when their careers are high-risk by nature? Education and youth activity providers confer an authority on those that enter into their space especially if they do not themselves foster young people’s critical thinking, or provide information to those that are interested in enlisting so that their decisions are fully informed. Should the far less regulated spaces that young people inhabit online – on social media and gaming platforms – be infiltrated by military organisations with their own interests to pursue?

The exceptionalism with which society perceives the armed forces – from what they say they can offer individuals that civil society does not, to what norms and legislation they are are exempt from – is also evident in how ‘exploitation’ of young people’s spaces is considered acceptable. Would other institutions and industries be given such access? That they fail in aspects of basic duty of care for vulnerable individuals, compounds the urgency of this issue.

In an important recent contribution to our understanding of the harm that military institutions impose on those who serve in them, academics Jonathan Parry and Christina Easton argue in their paper Filling the Ranks: Moral Risk and the Ethics of Military Recruitment that the risk of engaging in serious moral wrongdoing must be fully understood when considering how the armed forces engage with, and recruit, young people.

The authors start with this question:

‘If states are permitted to create and maintain a military, by what means may they do so?’

They interrogate the practices by which the armed forces maintain their ranks from the perspective of moral philosophy, looking at their activities in schools and other arenas exploited by the armed forces. They reason that being in the military is a ‘distinctively morally risky profession’, due to the nature of war and the actions it entails, such as killing, maiming, and destroying livelihoods. This creates a moral risk for the individual recruit which is exacerbated by the nature of the demographic that are targeted for recruitment.

There is also a moral harm committed by the state in placing this risk, and the moral responsibility of it, on young and inexperienced recruits. The moral burden is outsourced from the institution to the individual.

The authors carefully argue that a double moral wrong is inflicted. The risk for service personnel of committing a moral wrong themselves is high, especially in unjustified wars but even in justified operations, due to the risk of committing war crimes or inflicting disproportionate harm. But there is also a moral harm committed by the state in placing this risk, and the moral responsibility of it, on young and inexperienced recruits. The moral burden is outsourced from the institution to the individual.

Conclusion: operational and political demands are not enough

While young people are on the whole far more sceptical about military action, it is clear that this is only one of many factors affecting recruitment levels. The failings and demands of the recruitment system have left the majority who apply rejected and, for many others, the reality of military life does not live up to the illusory nature of its marketing. The cost to individuals in going down the wrong path, or living in institutions where they face significant stress or abuse and discrimination, is not given due weight.

Some material sources of dissatisfaction, such as pay and accommodation, are being addressed by this government, but the evidence suggests that the more entrenched cultural issues probably can not be meaningfully changed. These are doing significant harm to many, particularly women and girls, minorities and very young people.

There is a danger that the urgency of calls to fix the ‘recruitment crisis’, and even for some form of national service, could well eclipse these concerns about military harms completely.

While the Haythornthwaite report on ‘incentivising’ recruitment and retention has some perspective on how ‘old cultures’ of the military are problematic, it nonetheless presents solutions that prioritise operational demands and emphasise the same well worn paths to attract as many very young recruits as possible, with the attendant ethical concerns that these raise. The powerful testimony of personal experience and new perspectives that the research and moral thinking touched on here provide, are part of an understanding of military harms and risks which has developed significantly since the UK was involved in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. But there is a danger that the urgency of calls to fix the ‘recruitment crisis’, and even for some form of national service, could well eclipse these concerns about military harms completely. In responding to operational and political demands, we must recognise the social harms created by military institutions as part of the wider harm of military violence.

The current Defence Committee inquiry on the experience of women in the armed forces has the potential to refocus attention on pervasive issues of inequality, discrimination and abuse. This inquiry must also urgently address the negative outcomes for the youngest recruits who join as children, who are more vulnerable because of their age and factors in their background to the stresses of military life. The fact that they cannot be deployed until they are 18 is used to justify the UK continuing to recruit children against the better wisdom of the UN and numerous bodies, and UK public opinion, but this must not mask the harm experienced by many before deployment. At the very least, CRIN’s call for child protection measures at Harrogate to be put on a par with those in civilian institutions must be addressed.

See more: recruitment, recruitment age, risks, advertising, bullying and assault

Like what you read?

> Sign up for our newsletter or blog notifications

> Support our work – from just £2 a month