The MPs and the arms company reps

In November 2021 ForcesWatch released its first investigation into the Armed Forces Parliamentary Scheme (AFPS), an annual ‘course’ that purports to educate MPs and Peers about the daily experience of service personnel. To do so, the AFPS puts parliamentarians in uniform and lets them get tactile with tanks, helicopters and automatic weapons. It is as if MPs live vicariously through the Scheme, which presents a kind of martial optics for them to burnish their militarist credentials.

The Conservatives have traditionally enjoyed organic connections to the military and have always been well represented on the AFPS, but an ever increasing number of Labour MPs are taking part. Although this trend began long before Keir Starmer became leader of the party – and started appealing to the patriotism he believes is key to winning back the Red Wall – our analysis shows that many recent participants are on the Labour front bench.

This has a number of implications. Firstly, the Scheme further normalises close connections with – and a favourable ‘understanding’ of – the military as a prerequisite for elected officials. Secondly, with Labour high in the polls, there is a real chance that key brief holders in the next government will have been exposed to military and arms industry influence. And this influence does not have to be the overtly direct lobbying we hear about in newspaper exposes. It can come in the more subtle form of normalising the presence of arms companies in public life and seeing them as synonymous with the needs of our girls and boys in uniform.

Money for Nothing?

While in marketing terms the AFPS leads with military experience, it is deeply entangled with global arms firms: they have been the Scheme’s funders since its inception and two defence industry representatives sit on the AFPS Board of Trustees. Whatever else the Scheme may be, and whatever other functions it may serve, it has the potential to open routes of access to parliamentarians for defence companies. This is, of course, contested. When relaunching the Scheme as a charity in 2013 the current Chair of the AFPS, James Gray MP, told Parliament:

‘Traditionally, [the Scheme] has been paid for by the defence industry, and there have been four main sponsors. One of the things that I have been doing over the summer is going round all the defence companies, and I have now secured promises from at least 10 and possibly 15 of them—all the majors, such as Rolls-Royce, BAE Systems and Babcock, as well as others of a similar nature—each paying a small amount of funding, which will be sufficient to cover our anticipated costs.

‘The reason why that is a better arrangement is because, with 10 or 15 sponsors, we can say that none is achieving anything. Indeed, my pitch to them has been to say, “I would like some money from you, please.” They have asked, “What do we get back?” and I have replied, “You get absolutely nothing in return whatever. This is CSR—corporate social responsibility—for the defence industry. You get no lobbying, no access nor your name on writing paper, unless we choose to do so, but you get the warm feeling, Mr Rolls-Royce”—for example—“ of knowing that you have helped with the education of Members of Parliament.” All of them accepted that.’

To see how important the Scheme might be to sponsors it is instructive to look back at a previous – and equally important – expansion under New Labour in 1997. Until that point, the Conservative governments of Margaret Thatcher and John Major had been, by the admission of AFPS founder Neil Thorne himself, somewhat reticent to endorse the idea. His initial approach in the late 80s was deflected, and when finally excepted it was allegedly on the condition that it ‘must cost the taxpayer nothing‘. So, in the Scheme’s early years only a small number of MPs took part. As soon as Tony Blair came to power his Defence Secretary, George Robertson, called Thorne to offer full support and allow the AFPS intake to increase to 25 MPs. With this news, Thorne returned to the four sponsors he had at the time and they each ‘gave him a cheque for £30,000‘.

Guest List

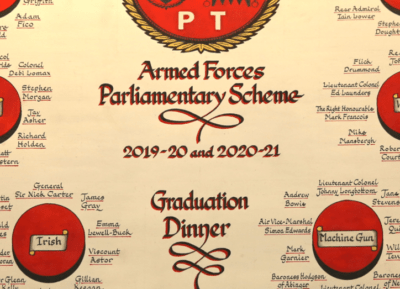

ForcesWatch can now reveal that a week before we published our first investigation into the AFPS, the participants of the 2019-20 and 2020-21 programmes gathered at the Guard’s Museum, near St James’s Park in London, for the annual dinner celebrating the Scheme’s recent graduates. With the pandemic halting plans for the 2019-20 cohort’s graduation ceremony, attendance was larger than usual. Thanks to a photograph of the seating arrangement published on the AFPS website, we can see, for the first time, who else was in attendance.

The photograph – which appears to be a hand-drawn document – shows six tables, each named after a current or disbanded Guards unit, around which sat a mix of MPs and Peers (the graduates), government ministers, military top brass and defence industry representatives. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these representatives were predominately responsible for their company’s relationship with governments. For ease of narrative and presentation, we will take each of the tables in turn, working anti-clockwise.

Grenadier Table

There were ten people sat at Grenadier, with the Conservative MP for Milton Keynes North, Ben Everitt, sitting in the 12-o’clock position. To Everitt’s left was Oliver Waghorn, Managing Director of Government Relations, Strategy & Business Winning at BAE Systems, and Advisory Board member at the Royal United Service Institute (RUSI) think-tank. According to RUSI, before joining BAE Waghorn served as a Special Advisor to UK Defence Secretary Liam Fox during the first 18 months of David Cameron’s coalition government. He also worked in Parliament providing research and policy advice to the Conservative Party’s Shadow Cabinet and was a research analyst for the MoD’s Defence Science & Technology Laboratory (DSTL). Waghorn previously worked for Interel Consulting – now part of Dentons Global Advisors – who are registered as a lobbyist with the Office of the Registrar of Consultant Lobbyists. According to Waghorn’s LinkedIn, while at Interel he supported Boeing, Leonardo, Lockheed Martin, QuinteQ and Babcock.

Also sat at Grenadier were John Gardner and Adam Fico. Fico is Head of Government Relations at Raytheon and was former Chief of Staff to AFPS Chair, and Conservative MP, James Gray, before leaving Parliament in March 2019 to join the missile manufacturer. During his time in Gray’s office, Fico was named as public contact for the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) for the Armed Forces (of which Gray is also Chair). As ForcesWatch have highlighted, the APPG for the Armed Forces has received over £500,000 from the defence industry since 2014. Whilst not amongst the biggest donors, Raytheon is one of the contributors (as are most of the companies represented at this dinner).

John Gardner’s LinkedIn history stretches back to roles in the Conservative Party and MOD (as Special Advisor) during the late 80s and early 90s, but he spent a sizeable chunk of his career as Group Head of Government Relations for Babcock International – a 14 year tenure at the company ended in March 2021. He is no stranger to the world of defence consultancy either, having provided advice to Lockheed Martin on a £1bn RAF contract whilst at Market Access Ltd in the 1990s. Since leaving Babcock, he has been a senior adviser to lobbying firm 5654, whose clients include private security contractor GardaWorld, and was a short-lived Special Advisor to Liz Truss’ Health Secretary, Therese Coffey. Gardner was an AFPS Trustee from 2018 to 2022, and in the role at the time of the Graduation dinner.

Former Labour Shadow Defence Secretary, Nia Griffith, also sat at Grenadier. Despite serving in the role under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn, Griffith maintained vocal support for NATO defence spending commitments alongside hawkish opposition to nuclear disarmament. Griffith is now Shadow Minister for International Trade. She was joined by fellow Labour MP, and Shadow Transport Minister, Tan Dhesi, as well as Conservative MPs Sarah Atherton and Anthony Higginbotham. Atherton is a military veteran and member of the Defence Select Committee, a body of MPs charged with scrutinising the expenditure, administration and policy of the MoD.

Scots Table

The Scots table was headed by Lord McNichol of Kilbride, a former general secretary of the Labour Party and graduate from the 2019-20 Scheme. Sat to McNichol’s right was Ben Carpenter Merrit, Head of Government Relations at defence firm Babcock International. Carpenter Merritt previously worked for Policy Connect, a cross party think-tank conducting a large part of its work through APPGs that is also listed with the Office of the Registrar of Consultant Lobbyists. Policy Connect’s client list is extensive and wide-ranging, with AFPS donors BAE Systems and Rolls-Royce featuring alongside tech firms, universities, NGOs and charities. Joining Merrit at the table was Airbus Public Affairs Manager Jay Asher, a reservist who previously worked in the office of Labour Shadow Health Secretary, and AFPS graduate, Wes Streeting.

Also present was Labour’s Stephen Morgan, who served as a Shadow Defence Minister from January 2020 to December 2021 and sat on the Armed Forces Bill Committee. It was the Committee’s job to examine and scrutinise the Armed Forces Bill as it passed through Parliament in the Summer of 2021. A few seats to Morgan’s right sat former colonel and Conservative MP James Sunderland, Chair of two military related APPGs (on Veterans and the Armed Forces Covenant), a former Private Secretary at the MoD, and Chair of the aforementioned Armed Forces Bill Select Committee.

Other figures of note on the table were AFPS founder Neil Thorne; Labour MPs Matt Western, a Shadow Education Secretary, and Fleur Anderson, the Shadow Paymaster General; and Conservative MP Richard Holden, who, like Stephen Morgan, sat on the Armed Forces Bill Committee.

Irish Table

General Sir Nick Carter, head of the armed forces at the time of the graduation dinner, sat atop Irish. He was joined by nine others including a senior Navy officer – Commander Susie Moran – and two defence firm representatives: Dr Glenn Kelly of Rolls Royce and, to Nick Carter’s right, Martin Fausset, CEO of Elbit Systems UK.

At the time of the dinner, Kelly was Roll Royce’s Head of Government Relations for Defence. He has since been seconded to work as an Executive Director at the UK Defence Solutions Centre (UKDSC). UKDSC is a collaboration between the British Government, the defence industry and academia that seeks to foster UK defence exports. Kelly has spent many years in the private and government military sector, including as Private Secretary to the Minister for Defence Equipment, Support and Technology, Head of Defence & Security Organisation for UK Trade & Investment in India, and senior advisor to NATO in the Balkans. Martin Fausset has led Elbit UK, part of the firm manufacturing most drones used by the Israeli military, for over six years. Prior to this, he worked at fellow defence manufacturers Rolls Royce, Ricardo and AgustaWestland.

Tory MP and AFPS Chair James Gray was also at the table. Gray’s own website describes his Territorial Army service and past roles on the Defence Committee and the Committees on Arms Export Controls. He previously chaired the Defence Sub-Committee on the Arctic from 2016 to 2017 and was appointed to the Joint Committee on the National Security Strategy in 2017. As mentioned above, he is also Chair of the APPG on the Armed Forces. To Gray’s left was Labour’s Emma Lewell-Buck, a shadow education minister who sits on both the Defence Committee and the Committees for Arms Export Controls. Her record in parliamentary debates on defence features strong criticism of the government over everything from Afghan resettlement to outsourcing, but little by way of criticism of the military itself. The table also seated Labour MPs Gerald Jones and Luke Pollard, who was appointed Shadow Minister for the Armed Forces in February 2022, alongside current Minister for Education Gillian Keegan (who at the time was a health minister).

Machine Gun

In something of an anomoly for the event, Machine Gun table had just one defence industry representative. Will Tew – who appears to go by the alias William T. on LinkedIn – works as Director of Global Government Relations and Public Policy at QinetiQ. He has been at the company for over 16 years, with an initial role as Public Affairs Manager in charge of, among others things, developing links with MPs at a constituency level. Tew is also currently an AFPS Trustee. Sitting either side of Will Tew was Conservative MP Jeremy Quin, then Minister for Defence Procurement, and Liberal Democrat Defence Spokesperson in the Lords, Baroness Smith of Newham – who is an AFPS Trustee. Quin’s ministerial duties included defence exports, and delivery of the military’s equipment plan.

Immediately to the left of Baroness Smith sat Lieutenant Colonel Mark Melhorn, a former British Army Chief of Staff who served as an adviser to Quin until March 2022. Mark Garnier, Chair of the Committees on Arms Export Controls, also dined on Machine Gun table, alongside fellow Conservative MPs Jane Stevenson and Andrew Bowie as well as the Conservative peer – and AFPS trustee – Baroness Hodgson. In October 2022, Bowie was appointed Under-Secretary of State for Exports with responsibilities that include UK defence and security.

Welsh Table

Welsh table was headed by retired Rear-Admiral John Kingwell, a Commandant at the Royal College of Defence Studies from 2019-2020 at a time when some of the graduates present would have attended the college as part of their course. Kingwell is now a member of the senior leadership team at global defence consultancy firm Universal Defence & Security Solutions (UDSS). According to UDSS, they ‘work in tandem with the MoD, FCO and Department for International Trade’, allegedly offering ‘the export of UK defence knowledge‘ including training provided to a group of Caribbean nations.

The table also featured retired brigadier Philip Pratley, currently Director of Trade and External Relations at Leonardo UK – an Italian defence firm arguably best known for its helicopters. Pratley was listed on the DSEI website as a 2021 keynote speaker on British military industrial strategy and, like a number of industry diners, is a member of industry association TechUK’s Defence and Security Board. We believe former Navy officer Mike Mansergh was also on Welsh table but that his surname was incorrectly written as Mansbergh. At the time of the event Mansergh was a Director of Strategic Engagement at AFPS sponsor Lockheed Martin, but his LinkedIn profile states that he is now retired.

Amy Swash, who replaced Adam Fico as James Gray’s Parliamentary Secretary and point contact for the APPG on the Armed Forces, was also at Welsh table, alongside former TA officer and Defence Select Committe member Mark Francois. Joining Francois were his fellow Conservative MPs Flick Drummond, Robert Courts, Fay Jones and Anne-Marie Morris, as well as the Ulster Unionist peer Lord Rogan. In October 2022, Jones was appointed as Assistant Chief Whip.

Coldstream Table

Sat in 12-o’clock position on Coldstream table is Wing Commander Greg ‘Vasco’ Smith, who currently oversees Parliamentary and Strategic Engagement at the MoD. Either side of Smith sat Labour MPs Stephanie Peacock and Louise Haigh. At the time, Peacock was Shadow Secretary for Veterans. Haigh has held various briefs in the Labour Shadow Cabinet under both Jeremy Corbyn and Keir Starmer, although none relating to defence (she is current Shadow for Transport). Haigh and Peacock were joined by fellow Labour Shadow Cabinet member Stephen Doughty, who is also a current trustee of the Armed Forces Parliamentary Trust.

To the right of Stephanie Peacock was General Dynamics Customer Liaison Director John Hiorns, who served in the British Army with the Royal Signals. Prior to joining General Dynamics, Hiorns worked for a year at the MoD’s Abbey Wood site in Bristol – HQ of the armed forces procurement body Defence Equipment & Support (DE&S). Also present was a guest named Jules Moore. We believe this is Julian Moore, Director of Government Affairs at Boeing UK & Ireland and a former Private Secretary to the Minister of Defence for Procurement. This was deduced by the fact that a Boeing representative is the only AFPS sponsor missing from the guests listed above. Coldstream also seated the Scottish National Party’s (SNP) David Linden, Conservative MPs Damien Moore and Robin Millar, and the Labour peer Lord Cromwell.

Maybe this dinner sets the groundwork for lobbying – much in the same way that the free pharmaceutical stationary handed out to medical professionals does.

The CSR Charade

A question hangs over the AFPS with regards to lobbying. Whilst James Gray insists arms industry sponsorship comes with a clear understanding that the scheme is a forum to educate, not influence, MPs, it is at least open to question why these companies would make such an undertaking – and despatch their government liaisons to the graduation dinner simply as a form of corporate social responsibility (CSR). Equally, whilst we cannot say that any of the defence industry representatives dining at The Guard’s Museum tried to influence parliamentarians over their evening meal, it certainly does present an opportunity to engage in fruitful conversation.

Another serious question is the number of MPs present at the dinner who sit on Parliamentary committees which scrutinise MoD procurement practices or arms export licenses. Other MPs on these committees are previous graduates of the AFPS and so it is reasonable to assume that they have attended similar events with similar guest lists. Our research suggests that the AFPS have held other events that also presented opportunities for access. For example, in 2012 The Times reported that representatives from AugustaWestland, BAE Systems, Capgemini UK and Rolls-Royce attended the Annual Reunion Reception of the Armed Forces Parliamentary Scheme alongside armed forces officers, MoD ministers and 52 MPs who had previously graduated from the Scheme.

How to Define Lobbying

The Commons and Lords each have their own codes of conduct with regards to lobbying. Parliamentary rules define lobbying as:

‘when an individual or a group tries to persuade someone in Parliament to support a particular policy or campaign. Lobbying can be done in person, by sending letters and emails or via social media.’

The difficulty here is of course knowing what was said at the graduation dinner – although perhaps this misses the point. When we take the definition of lobbying outlined above then we look for overt acts of persuasion. Those moments in which someone is clearly trying to pursuade or pressure a politician. But what if we see the dinner in a wider sense. As part of a process in which defence company representatives rub shoulders with MPs, humanise their companies and become a familiar face. Maybe this dinner sets the groundwork for lobbying – much in the same way that the free pharmaceutical stationary handed out to medical professionals does. But even if not, it still represents an opportunity for defence companies to reiterate the narrative that they are important providers of security and jobs.

This is important when we consider the large number of Shadow Cabinet members present. Whilst the vast majority did not hold defence briefs at the time, and do not hold them now, it still means that key members of the parliamentary Labour Party have completed a scheme that champions the close links between the armed forces and the defence industry. That is, even if companies represented at the event do not directly benefit from procurement decisions made by these Labour MPs in a future government, they have been given an opportunity to further develop their ‘social license to operate’.

The Network Effect

The power and influence of networks is also apparent when casting an eye over the guests. Campaign Against the Arms Trade (CAAT) has reported extensively on how arms firms extend their influence in government, the most obvious being the thousands of hours of meetings that have taken place between the government and defence firms. But CAAT also draw our attention to the revolving door, where civil servants and Special Advisors (SpAds) move seamlessly between Whitehall (or the armed forces) and the defence industry – examples of which are visible at the AFPS dinner. In this sense, the whole scheme should be seen as an extension of the military-industrial-complex, in which MPs are briefly invited inside under the pretext of building an understanding of the life of rank-and-file service personnel.

Without being privy to conversations taking place during the dinner events – and during the Scheme itself – it is impossible to know precisely what kind of interactions are taking place and what kind of relationships are being developed. We should question whether the AFPS is more than just an educational program for MPS and peers. And realise that it merits more attention than it has received from the press and campaigners alike.

See more: military in society, Armed Forces Parliamentary Scheme, UK Parliament, democracy, militarisation

Like what you read?

> Sign up for our newsletter or blog notifications

> Support our work – from just £2 a month