Rogue heroes?

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This article by ForcesWatch was first published in Peace News April-May 2023

The 22nd Special Air Service regiment, better known as the SAS, occupies a unique place in the British public consciousness. For many, it embodies notions of an elite level of valour and heroism coupled with the mystique of state secrecy and a certain roguish prestige.

Even within the military, these troops are often seen as almost supernaturally tough and skilled. A sense of barely-governed violence attaches to them, which results in nicknames like ‘blades’ and ‘pilgrims’.

The SAS mythology begins in the Second World War, but at various points the SAS ideal has been re-invigorated and re-shaped around particular operations or moments in military and national history. Two examples would be the Iranian Embassy siege in London in 1980 or the failed Bravo Two Zero patrol in Iraq during the 1991 Gulf War.

Contrary to its cultural impact, 22 SAS is a small unit estimated to have between 400 and 600 personnel. Until a change of policy in 2018 allowing women in frontline combat, the unit was exclusively male.

“The SAS exists at an odd point of tension in British culture, in that it is both intensely secretive and, at the same time, many of its activities are very well-known”

Based near Hereford in the West Midlands, the SAS is the largest element of UK special forces. Other special forces units include: the Royal Marines’ Special Boat Service, based in Poole; the army’s Special Reconnaissance Regiment and ‘special operations-capable’ Ranger Regiment (which was formed as part of the Future Soldier programme in 2021); a small constellation of support units from the Royal Air Force and parts of the regular army; and the Special Forces Support Group, which has personnel from across the three services.

The SAS also has two reservist units, 21 and 23 SAS. British special forces operate globally and also in a domestic counter-terrorism capacity. They are headed by a general with the title of ‘director special forces’, who occupies a senior position within the ministry of defence (MoD).The SAS is certainly the best-known British special forces unit. It enjoys vast budgets and, as we will see, a minimum of public and democratic oversight.

For a covert unit, it has been widely written about and reported on, though often in a manner which praises its achievements rather than critically studying its activities or culture. The SAS exists at an odd point of tension in British culture, in that it is both intensely secretive and, at the same time, many of its activities are very well known.

A lot of what we do know about the SAS is subject to a large amount of mythologising and artistic licence. Most recently, the regiment’s formative years during the Second World War have received star treatment.

The 2022 BBC TV show SAS: Rogue Heroes was generally well-received and enjoyed a substantial viewership.

A fictionalised account of the regiment’s foundation in North Africa in the early 1940s, Rogue Heroes attracted established stars to the cast including Jack O’Connell, Dominic West and Alfie Allen.

The first episode attracted 9.4m viewers and a second series is planned. The series is based on a book of the same name published in 2016 and written by The Times columnist Ben MacIntyre, author of popular military history books on topics as diverse as Napoleon and Colditz.

The series lionises SAS figures like Jock Lewes, Robert Blair ‘Paddy’ Mayne and SAS founder David Stirling – to whom we will return.

Watching the first episodes, the influences are very clear. The brutalised military masculinity, highly-stylised violence and maverick characters recall Peaky Blinders, the gangster series set in 1920s Birmingham. No surprise, then, that the two shows share a writer and producer in Stephen Knight.

But Rogue Heroes is just the most prominent and latest product of a thriving industry around what could be termed the ‘SAS-ification’ of culture, an extension of the Second World War nostalgia found in films like Dunkirk, but which chimes with contemporary appetites for rule-breaking role models, however flawed and violent.

“Stirling arranged a mercenary force of ex-SAS men to conduct a war of attrition in support of the Yemeni royalist regime”

Walk into any mainstream bookshop and you will find special-forces-linked books across various sections. The biography, self-help, fitness and fiction categories are dotted with books by SAS soldiers. The military history section seems to brim with them. There are (presumably ghost-written) novels by the same veterans, and books on how an elite forces mindset can supercharge different aspects of your life or physical wellbeing.

Many of the soldier-authors involved are household names. Andy McNab and Chris Ryan have been established since the 1990s, while figures like Jason Fox, Billy Billingham and the controversial Ant Middleton have built entire personal brands, businesses and small fortunes around SAS: Who Dares Wins, the latest in a long line of reality TV shows running back to the 2000s. In this sense, the SAS isn’t just an elite military unit, it is a popular cultural touchstone embedded in the public mind.

The endless churn of books and TV about the unit serve to further deepen a sense of pride in the SAS – a process which obscures more than it discloses. A deeper look at the SAS – and at its founder, David Stirling, in particular – turns up a history not of raffish rebelliousness but, far more logically, of deep allegiance to the British establishment and its global ambitions.

The real Stirling

A Cambridge-educated Scottish aristocrat and Guards officer, it should come as little surprise that Stirling was anything but a rogue. Except perhaps in the narrow sense that his Second World War senior officers viewed him as a reckless adventurer with maverick ideas about warfare.

Some of the men who joined his raiding unit in North Africa in 1941 were also unconventional. Robert Blair Mayne, for example, was supposedly found in jail and recruited by Stirling while awaiting court martial for striking a commander.

Despite early failures, the SAS had a series of successes in destroying enemy planes and attacking key targets.

Stirling was quickly promoted to lieutenant colonel but was captured in 1943 and spent the rest of the conflict as a prisoner of war, including in Colditz. He served on after the war as a reservist, retiring as a colonel in 1965. But it is Stirling’s long postwar career as a political agitator and private military expert which brings into relief his nature and loyalties.

Stirling was a pioneering figure in the private military sector. His Jersey-registered firm Watchguard International provided military services and expertise in the Gulf and Africa. Following a coup in Yemen in the early ’60s, Stirling was instrumental in arranging a mercenary force of ex-SAS men to conduct a sustained war of attrition in support of the ruling royalist regime, who were also backed by Saudi Arabia (see Declassified UK, 5 October 2022).

The five-year covert operation provided the opportunity for Britain to supply arms and fighter jets, and the training and ex-forces personnel to support them. This less-than-transparent partnership foreshadowed what is happening in Yemen today, and was likely a significant catalyst in the development of Britain’s arms trade with the Middle East, which has become a significant part of the British economy (see David Wearing’s AngloArabia, 2018).

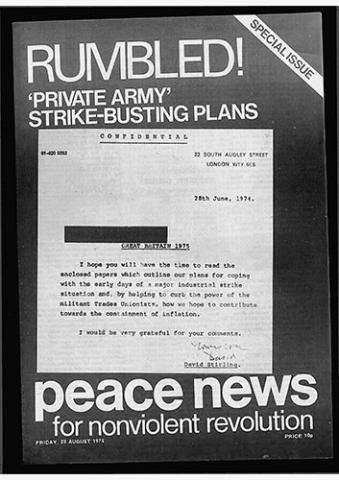

Cover of the Peace News special issue (23 August 1974) which exposed David Stirling’s attempt to set up a private army, ‘GB75’, which aimed to overthrow the government in the event of serious civil unrest.

An establishment loyalist, Stirling also took an interest in Britain’s internal affairs. This included an attempt to head off the trade union militancy of the 1970s. He founded the organisation GB75 (Great Britain 1975) as a strike-breaking force to back up the authorities and even step in to fill jobs in key industries (see PN 2664).

As Peace News noted, with its publication of secret GB75 documents in 1974, Stirling was a ‘liberal conservative’ – very much a man for the status quo, equally opposed to socialism and to the far-right (PN special issue, 23 August 1974). But Stirling’s anti-democratic strike-breaking plans quickly dissolved once exposed.

Abroad and at home

After 1945, the SAS operated in some of the most brutal battlefields of the withdrawal from empire. SAS troops served in places as far-flung as Malaya and Borneo (in South-East Asia) and Dhofar in Oman (bordering Yemen and Saudi Arabia) in anti-communist and anti-nationalist counter-insurgency campaigns. The regiment also featured heavily in the Troubles in Northern Ireland and was a key actor in the so-called ‘shoot to kill’ policy, in which suspected paramilitaries were killed without judicial process. Three unarmed IRA members were killed by the SAS in Gibraltar in 1988. A British inquest found the killings to have been lawful although the European court of human rights found that excessive force had been used.

It was during the conflict in Ireland that 14 Intelligence Company was formed. Also known as ‘the Det’, this plainclothes surveillance unit was deployed into communities to gather intelligence. According to some reports, it was later deployed to Yugoslavia to hunt war criminals. Today, its role is carried out by a successor unit, the Special Reconnaissance Regiment (SRR).

The SRR operated in Iraq and Afghanistan and also on home soil. In 2009, it was reported that the SRR was involved in the surveillance that led to the police wrongly killing Jean Charles de Menezes in the wake of the 7/7 London bombings. Over 20 years after the Good Friday Agreement was signed, the SRR is still reportedly being deployed in Northern Ireland to carry out surveillance on suspected paramilitaries.

Much of the SAS’s postwar activity has taken the form of advising and training foreign militaries and security forces, often in support of regimes with dubious human rights records.

SAS veteran Chris Ryan revealed that he had been involved in training the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. In Libya, SAS troops trained special forces of the Gaddafi regime in 2009 – only two years before the British military helped to overthrow the same government. Politicised deployments such as these certainly help to explain the desire for secrecy and unaccountability.

Unaccountable

British special forces activities are uniquely opaque when compared with the conventional UK military. The government holds to a strict ‘no comment’ policy on special forces operations when questioned in parliament, and Freedom of Information requests on special forces activities are exempt from disclosure on national security grounds.

The ‘no comment’ policy is usually referred to as ‘long-standing’. But research on the special forces by Declassified UK suggests it became a convention as recently as the 1980s, a Thatcher government response to the Gibraltar killings.

A 2018 report by the Oxford Research Group on Britain’s Shadow Army questioned the ‘complete opacity’ or lack of transparency that currently surrounds British special forces. The report argued that there should be some form of parliamentary oversight to help reduce the risk of ‘misdeployment’.

This was supported by a number of high-profile Conservative MPs. The research found that ‘Britain is alone among its allies in not permitting any discussion of the staffing, funding and the strategy surrounding the use of its special forces.’

The lack of oversight of British special forces is a major democratic issue, especially given their increasing use. But wider legislative barriers to investigation and transparency have also been introduced in recent years. These have implications for the accountability of the entire military, including Britain’s special forces – as recent controversies have shown.

Afghanistan

The Iraq and Afghanistan wars produced many allegations of war crimes by British troops. After years of campaigning by victims, their families and lawyers on one side, and pro-military MPs and ex-forces figures on the other, the government passed the Overseas Operations Act in 2021.

This legislation in effect provides a significant degree of immunity from war crimes prosecutions for UK troops. Despite being widely criticised throughout its passage through the House of Commons and the Lords, the act passed into law with limited revisions.

Though the likelihood of prosecutions may have diminished, the SAS’s conduct in southern Afghanistan continues to come up in the news.

In 2016, it was reported that army investigators were being obstructed by senior officers with links to the SAS.

“Iraq also produced scandals for the SAS – and a rare whistleblower, Ben Griffin”

In 2019, the BBC investigated claims that the SAS had killed three Afghan children and an older brother.

Then, in 2021, BBC Panorama produced a documentary and report based on internal SAS documents claiming there were up to 54 extrajudicial killings by troops during a single operational tour in the Helmand province of Afghanistan in 2010 – 2011. The report stated: ‘Individuals who served with the SAS squadron on that deployment told the BBC they witnessed the SAS operatives kill unarmed people during night raids.’ This included the practice of placing captured weapons on bodies to make them appear to be combatants.

General Mark Carleton-Smith had been director special forces at the time and was privy to information about the killings in Afghanistan. Yet, despite a military police investigation being under way, he is said to have not shared information about the allegations and to have allowed the same squadron to deploy for a further six-month tour in Afghanistan.

Military sources who spoke to the BBC suggested that ‘SAS squadrons were competing with each other to get the most kills, and that the squadron scrutinised by the BBC was trying to achieve a higher body count than the one it had replaced.’

Carleton-Smith later became head of the army and the allegations remain unresolved. The MoD has refused to comment beyond its standard statements about the courage and discipline of troops who served in Afghanistan.

Iraq also produced scandals for the SAS – and a rare whistleblower. Ben Griffin served in Iraq with the SAS before quitting the unit and emerging as a major anti-war figure. He detailed how the SAS, which was under US command in Iraq, carried out house raids in Baghdad. Many of those captured, he claimed, were nothing to do with the insurgency yet were handed over to Iraqi authorities to be tortured and imprisoned. Griffin was later gagged by the government in a secretive court hearing but went on to form Veterans for Peace UK, an ex-services peace organisation which campaigned against war and militarism.

Bullet holes left by an SAS raid in Afghanistan, 7 February 2011.

These clusters of bullet holes, low to the ground, suggest execution-style killings by SAS soldiers in Afghanistan, rather than the firefights that the SAS reported. Bursts of bullets seem to have been fired downwards from above – at targets low to the ground, perhaps crouching by the wall. That’s according to ballistics experts consulted by BBC Panorama in a 2022 investigation. These are walls of a guesthouse in the Nad Ali district of Helmand province, where nine men, including a teenager, were killed by the SAS, allegedly in a firefight, on 7 February 2011. Panorama found similar bullet hole patterns at two other locations where the SAS carried out lethal night raids. IMAGE: BBC PANORAMA

Pilgrims or ‘door-kickers’?

The SAS, and British special forces more broadly, remain an opaque and heavily mythologised institution. From their maverick origins in the Second World War and their current position as a cultural touchstone, they continue to enthral the public, despite their involvement in the dirty wars of the postwar era and in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The military culture industry serves a similar role to the so-called ‘copaganda’ (‘cop propaganda’) in TV police dramas. It glorifies, humanises and normalises war and military adventurism, rendering it palatable, even vicariously enjoyable to civilian audiences. In this sense, the military culture industry helps to recruit a viewing public to the pro-military or military-sympathetic view.

Behind this veneer, the special forces are the British state’s most prized ‘door-kickers’, to use the popular military vernacular. There is little to justify their status as ‘rogues’ since special forces are marked out by their commitment to discretion and obedience to the will of British governments. There are exceptions. Some positive, as in the case of occasional whistleblowers. Some profoundly negative, as in the case of alleged extrajudicial killings in Afghanistan.

It is not just possible but essential that we move past the mythologised public image of the British special forces that has conveniently filled the space created by a lack of transparency and a lack of political or military accountability.

This becomes more urgent as unscrutinised interventions in the ‘grey zone’ below the conventional threshold of war become the norm. It will only become more inappropriate to prevent greater public understanding and democratic oversight of what special forces, and the British government, are up to around the world.

See more: military in society, arms trade, culture, democracy, special forces

Like what you read?

> Sign up for our newsletter or blog notifications

> Support our work – from just £2 a month