Pushback? How Britain is militarising the Channel

In recent years the maritime movement of refugees and asylum seekers to the UK has become a touchstone topic across the political spectrum. One expression takes the form of moral panic, rooted in a language of invasion, that has allowed Britain’s militarised political culture to predictably position the armed forces as problem solvers. This came to a head in mid-January, when it was announced that the Ministry of Defence would assume oversight of policing migrant crossings in the English Channel – effectively putting elements of UK Border Force under military command and raising the possibility of regular naval patrols in the world’s busiest shipping route. However, military involvement is not new. Rather we are seeing an escalation of armed forces involvement that was catalysed by a Home Office request for MoD support in 2020.

Within days of sending its request, the Home Office also announced the creation of a new Clandestine Channel Threat Commander within Border Force. Tasked with overseeing plans for detering small boat crossings was Dan O’Mahoney, an ex-Royal Marine who served in Kosovo and Iraq. Now a civil servant, O’Mahoney most recently worked as Director of the Joint Maritime Security Centre (JMSC), an operation based in Portsmouth that monitors the UK’s territorial waters, and from which he would continue to work in his new capacity. Headed up by Army reservist Chris Chant, the JMSC leadership team consists of representatives from the Royal Navy, the MoD, Border Force and the Marine Management Organisation.

Looking back even further, it is apparent that the increased securitisation of other informal routes across the Channel has stimulated the use of small boats to land people on the coastline (although, ultimately, it is the lack of safe formal routes that are the problem). And criticism of the military’s use is not novel either. Our borders, as Drone Wars told MPs in a submission to the Defence Select Committee, ‘are not a war zone’:

‘…and civilians attempting to enter and leave the country are not armed combatants’.

Yet with the latest round of calls to centre the military in halting Channel crossings, our frontiers are becoming increasingly viewed as a battleground. The process may have began subtly, but the creeping militarisation of Britain’s borders, already felt by those seeking a new life here, is now out in the open.

Watching from the Air

Unpiloted aerial vehicles (UAV’s) are a staple of border militarisation worldwide and in November 2019 Portuguese company Tekever started flying their AR5 drone over the Channel under contract with the Home Office. In September 2020, Sky News’ Inzamam Rashid was given exclusive access to the control rooms at Lydd Airport in Kent, where Tekever were working alongside military personnel to fly surveillence sorties, in what what was journalistically framed as ‘an issue of national security’. As Drone Wars UK told the Defence Select Committee, the original Tekever contract ran from November 2019 to March 2020, but Government records show this has now been extended to September 2022. Additional submissions to the Committee also claim that a second Tekever drone, flown from Dover, is now in operation, while the Army has provided reconnaissance support with Watchkeeper drones. It was a Watchkeeper that stood in the hanger alongside Tekever drones in Rashid’s Sky News report.

The first known instance of a military aircraft flying in support of Border Force in the Channel came in August 2020, when an RAF Atlas stationed at Brize Norton in Oxfordshire provided survelliance and intelligence for Border Force and the Coast Guard. It came just a week after the Home Office request to the MoD for help in the Dover Straits, under a process known as Military Aid to the Civilian Authorities (MACA). The issuing of the MACA – which largely focused on aerial support – became a catalyst for the vertical militarisation of Britain’s border regime. Alongside the Atlas and the Army’s Watchkeeper, the RAF have used a Boeing P-8 Poseiden and Beechcraft Shadow R1. Prior to this, the only military involvement came on the surface of the sea when, in January 2019, two Royal Navy patrol boats were sent into the Channel to search for boats – in what appears to be the only such instance since crossing started.

The Barrack-isation of Detention Centres

Alongside the increasing use of military surveillance, the decision to use old army barracks as makeshift detention centres is further proof of the pattern of militarisation – an architectural manifestation of the disciplinary regime of the British immigration system in which the spectre of military violence (including the disciplinary violence of training) haunts the everyday experience of those seeking refuge. Napier Barracks in Folkestone, Kent, and Penally Barracks in Wales, were both “converted” into camps in a move that was resoundingly criticised by refugee and human rights organisations. A 2020 Guardian report described them as “squalid”, “unsanitary” and “unsuitable”, with The Helen Bamber Foundation’s Jennifer Blair telling the paper:

‘For a start, there’s a lack of privacy for showers and sleeping, and for survivors of rape and abuse that is unacceptable. [Penally] in particular looks really rundown, with bunk beds and concerns over social distancing’.

‘It is unacceptable to house survivors of torture and human trafficking in unsanitary and unsuitable conditions. The use of barracks as refugee camps has been done without adequate risk assessment, proper vulnerability screening and specialist trauma-informed healthcare’.

In March 2021 the Home Office announced that Penally would be closed but despite similar issues at Napier – a High Court judge even ruled it was unlawful to house asylum seekers there – plans are in place for the site to be used for at least another five years. And in February it was announced that a former RAF facility in Manston, Kent, was ready to start operating as an immigration processing facility for people crossing the Channel.

Law of the Sea

It was within this heavily militarised milieu that, on January 26th, two former Royal Navy officers appeared before the Commons Defence Select Committee to discuss the military’s involvement in the Channel – now known as Operation Isotrope. The senior figure was former admiral Charles Montgomery, who also led UK Border Force between 2013 and 2017. The second, Tom Sharpe (retd), had commanded Royal Navy patrol boats of the kind that could operate in the Channel. Committee chair Tobias Elwood was absent, but two other former army officers, the Conservative MPs Richard Drax and Mark Francois, contributed significant questions. However, Elwood did voice some scepticism at the potential use of the Navy after tabling an “urgent question” on the subject six days before the Committee met. Disappointingly, there was no serious discussion of the root causes of the refugee crisis – including the impacts of the UK’s military overseas – from which we would expect any profound analysis to proceed.

There was no question in the minds of the panellists that the military could do “the job”, but Tom Sharpe was keen to point out that it wasn’t clear what the job was beyond a current focus on cross-decking passengers out of rubber boats and into some form of maritime vessel:

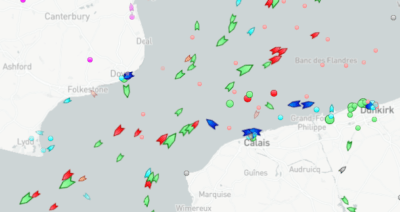

‘If we are talking about ensuring safe passage, which under article 98 of [the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea] all mariners are obliged to do, and the safety of life at sea rather than interdicting and taking otherwise safe migrants out of the water, that is one problem. If we are talking about ensuring that no one crosses without being detected and is then picked up on the shore side in the UK, that is another problem. In my view, that is a better solution, because it stops the idea of flooding the channel with ships, which could very easily make the problem worse’.

Sharpe pointed out that any ship could do the job of getting people out of one boat into another, because even the largest ship has its own fleet of small boats. He also emphasised:

‘This is the English Channel, remember. The minute you start manoeuvring your ship to launch boats, you are going to be in the way of very large vessels that cannot manoeuvre’.

Pushbacks and the Militarisation of Language

The creeping use of military language – particularly by politicians – is another node in the process of border militarisation. This was opitimised in the Committe hearing by Mark Francois, who asked about what rules of engagement (ROE) came into effect when a Navy ship encountered a refugee boat. In the military, ROE usually outline under what conditions – and to what degree – force can be used in a situation of violent potential. Tom Sharpe rejected this turn of phrase.

Tom Sharpe: ‘I am not even sure “rules of engagement” is the right term. This is a bit like confusing the inherent right of self-defence with rules of engagement. SOLAS [The Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea] and UNCLOS 98 are immutable requirements that are nothing to do with rules of engagement. The rules of engagement will be set from the centre. They are then defined by lawyers. As a note, they are never more permissive than the law allows. They are always slightly more restrictive. They define what you can and cannot do. What we are talking about here is what the ship does when it arrives at the boat’.

Mark Francois: ‘Yes, perhaps I should have just said “rules” rather than “rules of engagement”‘.

Tom Sharpe: ‘Yes, it is not really rules of engagement’.

When it was advanced by Francois, Sharpe also rejected the use of the term “pushback” in the context of refugee boats. It would, he said, be almost certainly illegal and unsafe:

‘I would be happy if the expression “pushback” were never used again. I cannot conceive of a situation where you are physically turning these ships back that is either legal or, perhaps more importantly, safe’.

Taking an increasingly hawkish stance, Francois also raised the use of “sonic weapons” to discourage boats. Sharpe’s response, based on his experience serving in the Gulf, verged on the comical:

‘It was quite good for flight deck parties as a loudspeaker, but it was really not much use as a sonic weapon. In fact, it was not even particularly useful to provide warnings to people that you wanted to turn away from the oil platforms. “Sonic weapon” is a misnomer. It is a large loudspeaker, which in my view is not particularly effective’.

Private Sector

Responding to a question from Richard Drax on privatising elements of the Channel response, Admiral Montgomery said the private sector had been used in the eastern Mediterranean:

‘We operated with the private sector in the east Mediterranean. You may not know, but we deployed two Border Force cutters to the Mediterranean at the height of the crisis. We took under control then two ships taken up from trade, as they are termed. They were fabulous enhancements to capability, really terrific, and integrated very closely. I did not sense that there were legal difficulties, as Tom has highlighted, in that operation. In the main, it was humanitarian, rather than enforcement. The private sector does have capabilities that I am sure can be well integrated’.

Sharpe, presumably citing mercenary operations against Somali pirates, was less convinced, though he did not completely reject the notion:

‘It can be done. Rather like when the private sector got involved with security operations off the Horn of Africa, it does pose command and control issues, legality issues and ROE issues. Under what regulations and under whose law are they operating? If you could bring private vessels in and control that satisfactorily so that liability, should something go wrong, was all accounted for, then why not? It does seem to me that you are now adding quite a lot of complexity’.

Sharpe also made the case for contracting a defence firm, SiriusInsight, to build a string of radar nodes along a stretch of the English coast. This would, Sharpe said, provide a permanent means by which to monitor activity in the Channel:

‘These nodes have radar, a thermal imaging camera, an optical camera, an AIS transponder and they can do some cell phone intercepts et cetera. You need about 10 of them. […] That is then the channel saturated forever. It persists forever. That is the real advantage of it over almost anything else’.

It should be noted that the UK’s record of privatising other areas of refugee and migrant infrastructure have not gone well. For example in December 2020, our colleagues at Corporate Watch published a report on the role of one company, Clear Springs, in providing extremely poor holding camps for refugees at Napier Barracks.

The ‘Australian Model’

While Tom Sharpe was the more critical of the two panellists, Montgomery did express some concerns – not least over command and control. He did, however, express a certain keenness on the Australian Model and its use of military personnel:

‘One should not draw absolute parallels, but if you look at the Australian model, which is quite often held up as being good practice, it has a two-star rear admiral working within the Australian Border Force. He or she has operational responsibility for the maritime effort off the Australian coast, drawing on a whole range of assigned Government assets. To my mind, that appears to maintain a very clear line of strategic responsibility set against operational responsibility’.

The notion that the Australian model – which is far more aggressive than anything currently carried out in the UK and hinges on internment in harsh camps away from the mainland – is “good practice” seems hard to square with human rights-oriented assessments. Refugees are taken to Manus Island, Papua New Guinea, or the island of Nauru. Human Rights Watch carried out interviews with internees as part of a report in 2016 and described them as follows:

‘These are no tropical island paradises, but offshore purgatory, where people endure a horrendous existence without hope for the future. Asylum seekers and refugees on Manus and Nauru have languished for years in dirty and cramped conditions in isolated detention centers with lengthy delays in refugee processing. Visits by Human Rights Watch to both islands found that refugees and asylum seekers have faced physical abuse, including sexual assault, harassment, intimidation, deliberate disregard for their health and safety, and uncertainty about their futures’.

The prospect of housing refugees in a third country as in the Australian model was touched on in the Select Committee session. Mark Francois asked Montgomery:

‘….the rumours are that “not allowing them to land on their own terms” is code, meaning that we will take them somewhere secure and the Government are trying to find some third country where we would take people to be processed. There have been rumours about Ghana and others. At the moment it would appear that they have not secured any such deal’.

In a lengthy response Montgomery touched on various aspects of the refugee response in the Mediterranean, only to return to Australia:

‘…but it is important to recognise that the deterrent effect in Australia is not simply in the massive distances involved nor indeed the very good regime it has for commanding its maritime areas, but also because anybody who was found was sent to a remote island with godforsaken facilities and people would stay there for a very long time before, in the main, they were sent back home. That is a deterrent that Australia is able to exert, which at the moment we cannot’.

Instrumentalising the Military

While there are obvious processes of militarisation happening in the Channel, and a clear desire for armed forces involvement from sections of the Conservative Party, there appears to be a lack of consensus within military circles on the role they will play now responsibility for policing the Channel lies with the MoD. For every Charles Montgomery there is a Tom Sharpe, sceptical of the parametres of the job and critical of the way politicians are overstretching resources. That is not to say those voices think the military is incapable, or should never be involved, but they are casting a more skeptical eye over the instrumentalisation of the armed forces by certain members of the Government.

Yet despite these voices, which suggest that the much-touted military solution is too nebulously defined, too lacking in resources and too close (in its current framing) to crossing into illegality, militarisation continues. And the more overt this becomes, the more people seeking refuge are framed as a threat to national security. This only leads to racism. Equally, by denying safe routes into the UK and making dangerous routes even more precarious, the British Government is putting lives at risk.

See more: human rights, legislation & policy, UK Parliament, border militarisation

Like what you read?

> Sign up for our newsletter or blog notifications

> Support our work – from just £2 a month