“It’s not a game”

Owen Everett, ForcesWatch

Each of the episodes from both series of Our War focuses on a different platoon or company, with varying missions during their tours in Helmand Province (which dated from between 2006 and 2012). Common themes to each of them include the youth of those involved, and the gravity of what is being asked of them.

The second series of the compelling Our War, on British Army officers’ and soldiers’ experiences of the war in Afghanistan, first shown on BBC Three between August and September, was repeated on BBC One last month. Like the Bafta-winning Series 1, first broadcast in June 2011, the three episodes consist of footage taken by troops of their patrols and time at their compounds, interspersed with interviews back in the UK with some of them and their relatives.

These soldiers and officers are almost all very young men, the youngest eighteen and twenty-three respectively. One of the platoons is nicknamed ‘Kindergarten’; another has an average age of twenty-one. Most of the soldiers in the first episode of series 1 (1.1) were still at school in 2001 when the Twin Towers were hit and the war started. Among the Welsh Guards in 2.3, one joined because he loved guns, and one joined because where he was from you either worked “in a chicken factory or go on the dole”.

The difference in the background of the officers and soldiers is very obvious. The 27-year-old officer in 1.2 (he looks younger) acknowledges that there “always has been an officer-soldier divide…that’s the way it works”, and an officer in 1.3 states that he wanted to be with the infantry to mix with people who might not otherwise be in his “social circle”. But although two officers confide about the burden and loneliness that they feel as being ultimately responsible for their men’s lives, they all have very informal, amicable relationships with them, one taking part in dance-offs around the ipod docks. The cameraderie and closeness in all the companies and platoons is very strong, and they have a lot of fun.

Photo: Christmas day lunch in episode 2.2 (BBC)

The opening of 2.1, partying on a Cyprus beach before deployment, reminds us how young they are. But the trauma of their experiences tests that joviality.

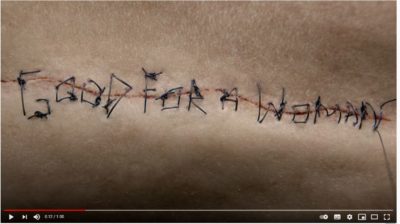

Our War offers a unique insight into the nature of contemporary warfare. At times I was exhilirated despite myself. It notes the great increase of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) from around 2007, and the obligation to “positively identify” the target as an armed direct threat as part of the rules of “courageous restraint”. The latter is frustrating for the men, but they acknowledge its importance in avoiding civilian casualties, one stating in 1.3 that if you shoot a civilian “you”re basically committing murder, aren’t you”, and that without courageous restraint “we”d be as bad as the Taliban”. Their thoughts on the combat are fascinating. In 2.3, one soldier talks of the pre-deployment desire to get your “first kill”; another in 1.2 admits his expectation of “going in like John Wayne”. In 2.2, one soldier says that fighting is “like being a kid”, but as the patrols become more dangerous his officer reiterates that, “It’s not a game”. One soldier reflects, “we”ve been trying to kill people. It’s really fucked up”, but stresses that he isn’t phased by the killing. Nor are another three, one stating that “it’s the norm”. In 2.3 one soldier refers openly to “giggling while we blow up Taliban”. Perhaps all this is unsurprising, given their training, the prevalence of often-glamourised violence in films, video games and on television, and the fact that in that situation – as one of them puts it – “one of yous has got to die”.

However, when British fatalities do occur – at least one is documented in each episode – reality “kicks in” and the horror of war is very clear. The 21-year-old soldier who dies in 2.2 was the 384th British fatality in the war. Several officers also die, demonstrating their similar vulnerability, even if in 2.1 control room struggle to understand who has been hit because they assume the casualty was not an officer. In an extremely moving scene in 2.3 the severely-injured officer is heard saying repeatedly “I’m going down”, to the vehement denial of his men (the helmet camera had been removed but was still recording). All of these deaths prompt the desire for vengeance, one soldier asserting that this can bring “closure”. Although we never see Taliban casualties, we do see civilian casualties: in 2.2 nineteen die when their minibus, headed for a wedding, goes over an IED. The troops feel guilty because it was primarily intended for them.

The men also reflect on whether the casualties and the war were “worth it” (the officer killed in 2.3 queried this in his journal). The Brigadier father of the officer killed in 2.1 questions if his son did die “in a good cause”, recognizing how (much more) terrible it would be if it wasn’t. Greatly moved, he says there have been too many deaths, but “as long as there are men and women…brave enough to step forward…we’re a nation to be proud of.” One soldier in the platoon asserts that it was “a great way to go”; another says that “you can’t really put a price on a life”. In other episodes assessments range from doubt (“He died for a road. It’s just a road. It’s not worth a life.”; “What have we really achieved?”) to pride and conviction that they had facilitated “growth” for Afghanistan and reduced “insurgencies”. Several of the men left the army after their tour. In 2.3 one admits to drinking heavily back in the UK, and other was discharged with a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder. However, others remained, a soldier in 2.2 telling us that he, “just can’t wait for the next one really.”

The government has committed to the full withdrawal of British troops from Afghanistan by the end of 2014, but the company in 2.3 who only returned from their six-month tour in March found that the war was “far from over”. The continuing loss of life – many of them so young – is incredibly upsetting.

See more: risks, culture

Like what you read?

> Sign up for our newsletter or blog notifications

> Support our work – from just £2 a month