From Militant to Military Labour

The UK is experiencing a period of industrial militancy. Transport workers, dockers and postal workers have all been out on strike in recent weeks. Even barristers have taken to picketing, while nurses and firefighters are balloting on walk-outs. Strikes invariably inspire reaction, in every sense of the word. One mode of that reaction, especially when strikes shutdown key industries or public services, are calls to summon the army as “scab” labour to keep vital services running.

The practicalities of bringing in soldiers to run the ticket barriers at Euston or Lime Street, let alone operate trains, should be enough to put anyone off. And yet the calls emerge each time, especially on social media. And in truth, the British military has stepped in during periods of militant worker’s activity in the past. Generally, they do so in one of two ways: the first, to break strikes with force, actual or implied; and secondly, to literally step in and take over jobs worker’s have withdrawn their labour from. We will examine both, as well as the prospects for them reoccurring now.

This is relevant not only because of the current climate of organised labour activity, but because of the increasing lionisation of the military in public life during the transition to power of a fourth Tory prime minister in 12 years. Liz Truss has pledged, among other things, to increased defence spending whilst also threatening to pin back workers’ rights – in effect crushing the effectiveness of unions.

Glasgow to Liverpool

At one time the British military had a policing role. It was routinely used to violently suppress movements like the Luddites, but its most famous outing was probably the event known as the Peterloo Massacre. In 1819, the local yeomanry rode, sabres swinging, into a mass protest at St. Peter’s Field, Manchester, leaving hundreds injured and 18 dead.

Since the foundation of a domestic police force in 1829, followed by a distinct internal security force (MI5), strikers and protesters have increasingly faced civil rather than military authorities. Thus, with a few exceptions, the general pattern of the late 20th century is that the police deal with strikes, albeit at times extremely brutally, and when the military are summoned to intervene it is largely as scab labour. The caveat being in the waves of worker unrest before WW2, when the military was employed to physically break up strikes with often drastic consequences.

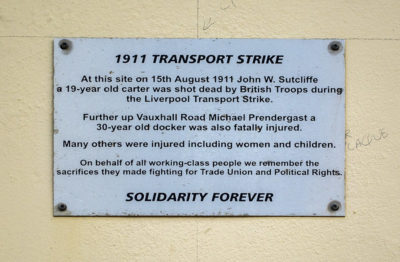

The largest industrial action in British history was the 1926 general strike, which centred on miner’s hours and pay but pulled in virtually the entire British working class. In that case anti-strike volunteers and the army were deployed to run, and protect, key transportation routes, printing presses and factories. After nine days the action ended in defeat for the strikers. In 1911, two workers were shot by soldiers in Liverpool amid riots arising from a major transport worker dispute. A warship was even docked in the Mersey and a van containing arrested strikers was attacked. Up to 50,000 troops were mobilised nationally at the time, though rail strikes made moving them across the country difficult. A year before, troops were deployed by Winston Churchill to support police during riots and strikes in the mining town of Tonypandy, south Wales. One civilian death and hundreds of injuries resulted from the clashes.

In 1975, as the role of the military shifted, soldiers were called in to clear refuse during a binmen’s strike in Glasgow. They were paid an extra 50p a week up until the strike ended in April. While in 2002 firefighters struck over pay and the army rolled out ageing Green Goddess fire trucks to fill the gaps – the very same trucks they had used to break another firefighter strike in the 1970s. Although hugely damaging to worker power, these recent examples enabled the military to distance itself from violent attacks on strikers and rebrand as an institution that helps keep the economy running.

The same logic governs the military’s keen use of civil intervention to repair its reputation over Iraq and Afghanistan. From building Nightingale Hospitals and administering vaccines during the Covid pandemic, to ensuring fuel deliveries amidst HGV driver shortages – the military loves an opportunity to sanatise its image. ‘Good news’ matters to the Ministry of Defence, so, conversely, any violent intervention against striking workers seems like a gauarentee of precisely the kind of bad optics the military wants to avoid.

From militant to military labour

In a sense, the military is ready-made for breaking strikes. Personnel have vastly reduced rights themselves and are not allowed to unionise, and, while the ranks are overwhelmingly drawn from the working classes, potential solidarity is carefully eroded. Historic ruling class fears that military personnel may side with their own class are offset by the creation of civilian police forces and, in the British Army, for example, deep conditioning in training which encourages personnel to be contemptuous towards civilians.

The prospect of a unionised military is small, though from time to time it reappears. Labour’s 2019 manifesto pledged to consult on a federation, in effect a union without the right to strike, and the idea was raised again by Labour and the Scottish National Party when the Armed Forces Bill passed through Parliament in 2021. It is something ForcesWatch have also explored in previous blogs – arguing that a more radical approach to Labour’s Police Federation model is needed. Nevertheless, there is a tendency for people inside and outside the military to view service personnel not as exploited workers, but as a separate class of people entirely.

Prospects

Some would claim that we are in a period of class conflict which echoes the conditions around the interwar period. The cost-of-living crisis, conflict in Europe, failing markets, increased inequality, and febrile politics are making themselves felt daily. There is discussion in some quarters of a general strike, though one is left wondering whether the scale of militancy required to achieve such a feat – essentially a total shutdown of the country – is widely understood. Trade union laws today are very restrictive and the confidence of workers’, while on the increase among some unions, is not where it was in 1911 or 1926.

It could be the case that a general strike does occur at some point in the next few years, and in that case the military – non-unionised and de-linked from the social class from which it is drawn – steps in. There is certainly a constituency for this kind of reaction, at least online. But it does not seem to be the case that this is something which is rapidly approaching. And it seems likely that the military itself, fresh from intervention into civil affairs as part of the pandemic response and extremely sensitive to reputational damage, would particularly favour stepping in to fill the void. But it would take a far greater degree of labour being withdrawn before the military, much reduced in recent years, was called in. And it is unlikely it would make much of an impact given the existing demands on its personnel numbers.

Read our case for unionising the army here.

See more: military in society, public relations

Like what you read?

> Sign up for our newsletter or blog notifications

> Support our work – from just £2 a month