Day One, Week One: Veteranhood

Tom (anonymised) describes the shock of capture that accompanies the early days of military training:

‘I remember lads who were MMA fighters and rugby players, tough kids, fit enough, but they put their chit in [left training]’.

Tom was in an elite infantry unit but he recognises that the intial processes by which we are trained are experienced broadly similarly across the military. I was not in the infantry, for example, but most of my military instructors were. There may have been a difference in the length of basic training from service to service, or between reservists and regular personnel, but the methods and aims are the same, at least to the degree that it matters for our understanding. Tome joined nearly a decade after me but he describes the same breaking-down processes:

‘Things like the mental stuff, change parades [where you are forced to change uniforms again and again as punishment] and all that, they would have done that in all the units, there’s that mental aspect’.

This breaking down is accompanied by a stripping away of civilian identity:

‘They made you shave your head but it’s not like a shaved head. It is a number three, so you have that awkward length, so you all look like fucking idiots, and that was one thing that looking back on, when you all look the same, I always had a bit about me, soon as I had that number three I was like I’m fucking no one now’.

Gav was in a Scottish infantry regiment and makes a broader point:

‘The training, I feel, obviously works to benefit them. But based on the idea that they want to grind the individual down as far as possible, without breaking them mentally, but I think it is very boarderline because some might be broken down at times’.

We do not come into the ranks as blank slates onto which military ideas are etched. Socio-economically speaking recruits to professional armies are generally, as I have said, low-end material, those already harried by life at the sharp end of capitalism. As one veteran pointed out, even to join the army, to leave family and friends behind, you would be likely to have attachment issues.

Years ago, at an anti-war veteran meeting in a converted barn at a blustery farm in Devon, a former Royal Engineer-turned-social worker named Mike told me that in any other context large parts of training and military culture would amount to domestic abuse. This struck me as an incredibly strong statement, and yet he was something of a subject matter expert, having worked around people affected by precisely that issue for many years. I tracked him down and asked him to reiterate over Zoom:

‘If you look at the legislation, what the CPS describes as domestic abuse: controlling, coercive and threatening behaviour, ages sixteen and over, intimate partner or family members. You can easily argue that the army is your family, as many people do’.

That is more or less exactly what the definition says. Mike is also right that the army is family, the military markets itself as precisely that. Belonging and meaning, as well as advancement and adventure, have long been features of recruiting campaigns in the UK. The idea of a “regimental family” is a powerful current in military identity as well as an organising framework and a source of solidarity and aid in post-service life. But if the army is a family, it is a dysfunctional one, at least by any civilian measure. Of course, by its very nature the military enjoys exemptions from the rules of civilian life and operates beyond the parameters of civilised normality. Maybe this is necessary on the grounds of defence of the nation, but that is not the question here. The point is whether this accounts for our subsequent composition.

It is an in-joke in the military that someone could claim to get PTSD from training, though objectively it is completely possible. Likewise, the urban legend of a dumb recruit who has cracked, ineptly trying and failing to hang himself with a bungee cord, seems to be shared across all three services. But these are not what I am talking about here, rather I am referring to the intense program of social engineering which the military carries out for its own benefit.

There is a certain duality at play here that we must grapple with. Many veterans, and I include myself in this, will also tell you that some of their best memories of the Mob are from basic training. Thise first twelve weeks or so were exciting, terrifying, challenging and fun. You feel like you are part of something important, adventurous and somehow old-fashioned. I found it at once completely shit and deeply compelling, a tension which, if I am honest, has coloured my relationship with the military ever since. Training is also psychically damaging, as is the further training you do in your unit. The general immersion in military culture takes a toll. Both things – the almost hedonistic, self-developmental positives and the exacting, spiritually costly negatives – are true at once.

Despite these contradictions, I am sure not every veteran is about to explode into a murderous rage. To say so would be unhelpful and wrong-headed, a product of mostly war movies and one-dimensional reporting. I think it is fair to say that military veterans are wound tighter and run hotter than civilians. I am not talking about military experience, as some veterans do, as if it is a superpower. Far from it. I also note, we run hot whether or not we have been to war, fired a weapon in anger or seen our comrades die, though those experiences are thought to “embed” our training deeper. War trauma ices the cake but some of the most serious military harm, I contend, occurs not in dusty theatres of war but in those little fenced-off corners of Britain where civilians mostly cannot go. In barracks and on training areas, through the formative months of our new military existence and then on through the career-long cycles of training and exposure to military culture, where our souls are made to spark on command.

I do not know if the grim-faced corporals and sergeants of Army Training Regiment (ATR) Pirbright knew about Napoleon’s view on soldiering quoted at the start of this chapter. My feeling is probably not, and I can hardly brag because I certainly did not either, but that they saw their task as running a charge through us was never in doubt. Their phrasing was a little different, but the spirit was the same. ‘You had better start fucking sparking, you c**nts’, they would scream at us whenever we failed to conduct ourselves with the urgency that befits a soldier in the British Army. Every task, they told us, had to be conducted with the speed of “ten tall Indians” or “a thousand gazelles”.

The pattern consistent throughout is the sharp yell, the rapid response, repeated again and again until we snapped into motion or stillness, silence or aggression, as the command dictates. This develops over time until you respond to each sharp order as if it is the crack of a rifle, commanding you to apply your belt buckle, and your body, to the earth. ‘You’ll be digging with you eyelids when it happens for real’, our section commander, a dry-witted Coldstream Guards lance-sergeant latter killed in Afghanistan, would tell us.

This is a Pavlovian process. Hitting the required standard lets you breathe for a moment. It pays to be a winner, the screws would tell us. At week six, for example, if we had learned how to march well enough, we got to go home for a weekend and thereafter we could march ourselves (rather than be marched as a squad) to the scoff house for our meals. If we had not started to master our halts and turns and various other skills we faced being back-squadded – sent back a week to retake the lessons with the troop of recruits we did not know, with whom no bonds had been established, under a new batch of NCOs who would view us poorly for having been foisted onto them. Training about learning through pain and fear.

The military and its outriders usually talk about training in terms of fitness and skills and as a process of building resilience and inculcating a new culture. They also talk about it in terms of values. For the army, these were embodied in CDRILS: Courage, Discipline, Respect for Others, Integrity, Loyalty and Selfless Commitment. We learned these British Army Values and Standards from the Padre (a military priest) over those first rough weeks in uniform. These were reiterated by our roaring training screws (military instructors share a nickname with prison guards) whenever we were felt to have transgressed them, because, as we were reminded daily: ‘You aren’t fucking civilians now, lads’.

Those of us who are “critical” veterans have some to recognise deeper processes at work. In short order, that the military must speak to, revise and occupy our souls. Veterans for Peace UK, the UK wing of an American anti-war vets organisation around which many of us coalesced in the 2010s, advanced a profound analysis of what training does, based in part on the ground work of US Army Ranger and psychologist Lt Col David Grossman. As one veteran, who joined as a boy soldier and was “blown up” in Afghanistan, wrote:

‘It was not combat trauma that led to any of my mental health issues or returning to a civilian life. It was the training itself. It is this discovery that made me realise that it is not just battlefield trauma that causes mental health issues but the conditioning associated with training have a massive part to play’.

In the Veteran’s for Peace reading, the military must a) remove the barrier to kill, b) ensure obedience without question, and c) instil loyalty to the gang. Veterans for Peace also advanced a theory we came to call the “hierarchy of contempt” or “hierarchy of hate”, in which the civilian population from which we ourselves were drawn was the most reviled. In the intervening years, another analysis, deeper but with considerable crossover, has spoken to me. To paraphrase its main figure, whose work we will now turn to: the army must change you inside.

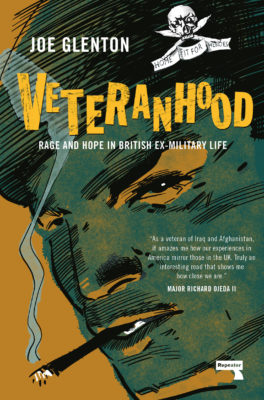

Joe Glenton works on press and communications at ForcesWatch. Veteranhood is out now via Repeater.

See more: mental health, recruitment, veterans, mental health, training

Like what you read?

> Sign up for our newsletter or blog notifications

> Support our work – from just £2 a month