Dark Matter: The UK military ventures into space

In August this year, the Ministry of Defence launched its first ever spy satellite into orbit from Elon Musk’s SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket lift-off in California. Named after the Greek goddess of fortune, ‘Tyche’ is an earth-imaging satellite capable of capturing objects larger than one metre from its position in lower-earth orbit (roughly 5,000km into space).

Tyche will provide the UK armed forces with high-speed ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance) data, and is the first of the MoD’s ISTARI project, which intends to launch an entire constellation of ISR satellites over the next ten years. Tyche’s inauguration was celebrated as a symbolic moment for British defence, marking ‘the end of the beginning for the UK space command’.

Galactic Britain

Although the UK’s space programme started in 1952, it remained a relatively small player in the domain compared to other states like the US, China, Russia, India, France and Japan. However, in the past five years, British defence in space has taken off exponentially.

‘As our adversaries advance their space capabilities, it is vital we invest in space to ensure we maintain a battle-winning advantage across this fast-evolving operational domain.’

The Conservative party turned its attention to space during the 2019 election campaign after NATO declared space, alongside cyber, an official ‘operational domain’. After winning the election, Johnson’s government delivered on its pledge to establish a UK Space Command, which was launched in 2021 and shortly followed by a National Space Strategy and Defence Space Strategy. Johnson said ‘[in] a plan that will see us take a leading role on the international stage, Global Britain [is] becoming Galactic Britain’. The Command was awarded £1.6 billion over ten years, and the defence procurement minister at the time affirmed the government’s ambitions: ‘As our adversaries advance their space capabilities, it is vital we invest in space to ensure we maintain a battle-winning advantage across this fast-evolving operational domain.’

The opening of UK Space Command HQ in High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire was followed by a memorandum of understanding with the US (ESC-MOU) which consolidated the sharing of space information, capabilities, training exercises and wargames.

U.K. Space Command headquarters is located at RAF High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire. Crown Copyright, MOD 2021

Defending ‘in, from and to space’

The UK space command is a joint command led by the Royal Air Force (RAF) but staffed by personnel from the British Army, the Royal Navy and the RAF, as well as civil servants and contractors.

Its mission is ‘to protect and defend UK and allied interests in, from, and to space’. Potential threats in space will be monitored through a network of existing and proposed deep-space radars in south Wales, which survey deep into the sky from earth. Despite information being sparse, it is likely that UK Space Command will be monitoring some of the 600+ U.S military satellites, and have a close eye on the hundreds of dual-use satellites which they share with their commercial partners.

Satellites, despite being vital for everyday civilian and military life (including communications, navigation, banking and internet), are increasingly vulnerable. In Ukraine, Russia has reportedly jammed western satellites – inhibiting Ukraine’s ability to operate high-tech weapons. This isn’t the first time Russia has been accused of satellite jamming.

Anti-satellite weapons (ASATs) have been tested by frontrunners in the so-called ‘space race’ as a demonstration of prowess and capability. The US was the first to launch an ASAT in 1985 from an aircraft and then later in 2008 from a ship. China tested it in 2007, India in 2019, and most recently, Russia fired ASAT missiles in 2020 and shot down a satellite in 2021.

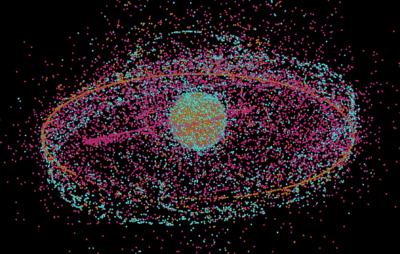

Another serious threat to satellites is the risk of collision with so-called ‘space junk’ of which over 30,000 pieces of debris currently orbit earth. In a worst case scenario, experts are concerned that a single major collision could set off a chain reaction that will ultimately endanger any vessel orbiting the planet. The ASAT tests were criticised for dissipating thousands of pieces of trackable debris, which in one case caused astronauts to take shelter in the international space station as an emergency precaution. According to Pentagon advisor Brad Townsend, ‘If nations start arming with ASATs … they risk creating a new form of mutually assured destruction’.

As well as looking towards the sky, the UK command will be analysing data received from its friendly satellites that gather earth-based intelligence and surveillance imagery, such as information about enemy infrastructure or positioning on the battlefield. Satellites also monitor others satellites (to try to work out what they are doing) and their proximity to space debris or adverse weather conditions.

Image: From For Heaven’s Sake’, published by CND and Drone wars in 2022.

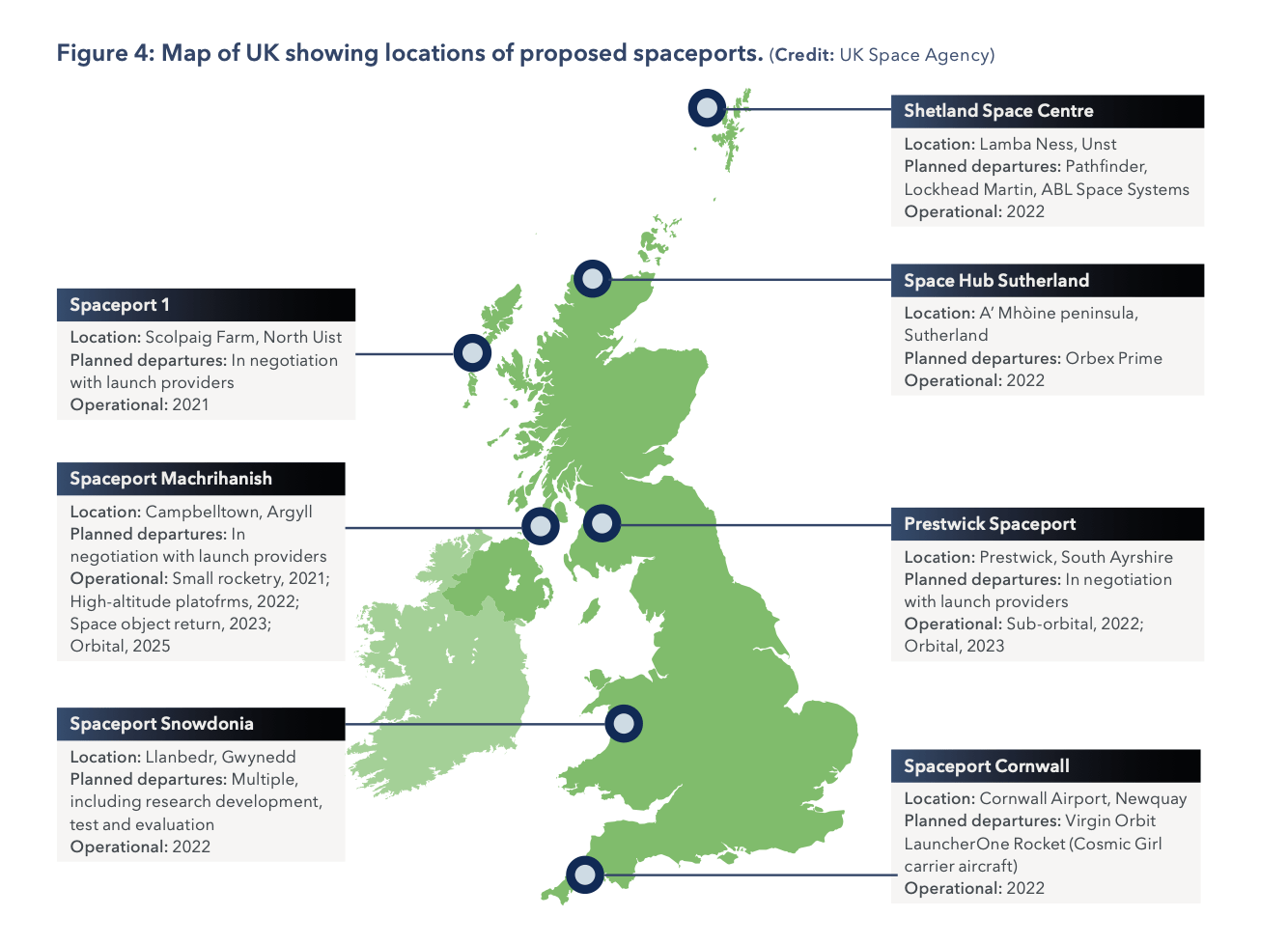

Finally, the UK has huge plans for its own journey to space, through the proposed network of spaceports. At the moment, the UK Command relies on its allies to access the orbit, however, it is in a race to become the first place in Europe that can facilitate rocket launches, with the major Saxavord site well underway in the Shetland Islands.

A military framework

Space Command personnel wear camouflage uniforms with a custom ‘UK Space Command’ badge, whilst working their computer-based battlefield. They conduct military wargames and operate under a military-style chain of command. The RAF are in charge of recruitment to the Space Command, with roles requiring a 6-stage compatibility test followed by 24 week military training. Subsidised food, accommodation, gym and travel are the benefits of joining, and current enlistments range from ‘Intelligence Officer’ to ‘Air and Space Operations Specialist’.

The RAF proclaims itself as one of the largest providers of apprenticeships in the UK, so if candidates fail the entry requirements there are other routes into the Space Command. The National Space Academy is a partner of the RAF, and regularly visits schools promoting space-based careers for young people, as well as a wide range of outreach including summer camps and teacher training.

Major General Paul Tedman was appointed the new head of the UK Space Command on 17th August 2024, the day after the launch of Tyche, which he described as ‘a fabulous day for UK space’. Tedman served in the RAF for over 25 years before moving to the United States Space Force in 2021. He has essentially swapped with Paul Godfrey, who stepped down as head of the UK Space Command to take up a post in the US Space Force, working in the Pentagon as a strategic advisor to the chief of space operations. The chief said: ‘RAF Air Marshal Godfrey’s arrival is unprecedented, and it pushes the boundaries of what it means to be integrated by design.’ Godfrey responded: ‘This is an exciting and unique opportunity to bring an allied space perspective into the heart of the United States Space Force and assist in operationalising the “Partner to Win” Line of Effort.’

A ‘sovereign’ space mission or ‘integrated by design’?

The government’s press release for the August launch of the Tyche satellite appeals to a sense of national pride cloaked in sovereignty with the public encouraged to uncritically support, even celebrate, the UK’s flying head-first into an arms race in space.

Tyche was seen as a milestone for UK space. This is not because of its intelligence gathering and earth-imaging functions, as the UK has accessed the same kind of information for decades in ‘a friendly request to allies, particularly the United States’. Rather, it was the assumed sovereignty of a British-made (by Surrey Satellite Technology Limited – SSTL) and ‘fully’ British-owned military ISR satellite that excited the media and commentators. The launch of Tyche provided a strong pat on the back for the MoD and its contractors, with Tedman commending that they ‘can rapidly take a concept through to the delivery of a satellite capability on orbit.’

The government’s press release for the August launch of the Tyche satellite appeals to a sense of national pride cloaked in sovereignty with the public encouraged to uncritically support, even celebrate, the UK’s flying head-first into an arms race in space.

The UK military does already have its own satellite constellation, Skynet, of which iterations have been used by the armed forces since the 1960’s. Currently operated by the contractor Babcock International, the Skynet system provides strategic and tactical communications services to the UK armed forces and allies. Curiously, the launch of Tyche was commended as a groundbreaking moment for the Space Command without recognising that the UK has operationalised space for military purposes for decades.

Efforts to present the UK as a new or independent actor in space are unsubstantiated and largely rhetorical. They attempt to harness public support for ‘defending our nation’ whilst avoiding proper scrutiny of the moral or political implications – and processes – of militarising space.

The launch, and any other output from the UK Space Command in fact, cannot claim to be ‘sovereign’ or fully independent from its allied partners. In a September 2024 article entitled ‘UK-US integration key to future of space security’, the US space force confirmed this interdependence. A visiting US Command team went to RAF Waddington, Feltwell and High Wycombe in a trip that was crucial in ‘emphasising the importance of our allied partnerships’ and ‘furthering the force’s integration with the UK’s national security space program’.

U.S. Space Force Lt. Col. Danielle Amason, 73rd Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance Squadron, Detachment 4 commander, gives a tour to U.S. Space Force senior leaders, during a visit at RAF Feltwell, UK, Aug. 28, 2024. (U.S. Air Force photo by Senior Airman Renee Nicole S.N. Finona)

A series of treaties have enshrined this relationship too – including the US ‘Operation Olympic defender’ and aspects of the AUKUS security pact. The UK has long-established US military bases in its territory, including Menwith Hill, which is the largest intelligence-gathering, interception and surveillance base outside the US. We are so deeply embroiled with the US in space that it would not be an overstatement to say that the UK space force is a European extension of its US counterpart. The UK’s approach seems to be about adding value to the US Space Force, endorsing its mission to ‘dominate space’, rather than attempting to challenge it.

Efforts to present the UK as a new or independent actor in space are unsubstantiated and largely rhetorical. They attempt to harness public support for ‘defending our nation’ whilst avoiding proper scrutiny of the moral or political implications – and processes – of militarising space. Framing the matter as one of national security grants even more secrecy, and military commanders are entrusted to lead with a laser-focused military mindset that treats space as just another war-fighting domain.

The sky’s the limit for profiteers

The Ministry of Defence partnered with the Air & Space Power Association in September to host the Defence Space Conference 2024, which is described as ‘The UK’s leading defence space event’. The conference was hosted in collaboration with ‘strategic partners’ BAE Systems, Palantir, Raytheon and Airbus. Sponsors included Thales, Babcock, Leonardo, L3 Harris and Lockheed Martin – some of the largest arms companies in the world. Broadly, it sought to deepen the integration of western governments, militaries and industry to maximise the capacity of defence in space. The event opened with a series of dramatic videos including one by Palantir assuring that the company is ‘helping the West to win in space’.

Minister for the Armed Forces Luke Pollard addressed the conference as a keynote speaker, and he started by assuring the audience that ‘I want you to know that space is omnipresent in my thoughts’. After hyping up the strategic and economic importance of defence in space, he directly posed what seemed like an alarming simplistic call to arms: ‘I like to set my audiences homework. So as you gather, from allied countries, businesses, and institutions, my homework is for us all to come together and put rocket boosters on our collaboration. To ensure those who believe in universal freedoms and a rules-based international system, win the 21st century space race.’

The speech ended by encouraging audience members to contribute to Labour’s current defence review, which emphasises the centrality of the private defence and security industry to government policy. Campaign Against Arms Trade’s new report on the closer than close relationship between the UK government and the arms industry suggests that space is one domain amongst many where this blurring of commercial and state lines exists.

The Air & Space Power Association has already planned member events such as ‘fire-side chats’ and industry dinners before the end of this year. In Westminster, the All Party Parliamentary Group for Space (p752) provides another site for collaborations between defence space profiteers and the government. The secretariat for the APPG is provided by ADS, the trade association of the aerospace, defence and security industry.

Despite having unprecedented access to our democratic representatives and institutions, these companies are not democratically accountable and at the end of the day, answer to their profit-oriented shareholders. Major arms firms rely on the narrative that militarisation (including in space) is necessary to keep us safe, in order to guarantee a future market. They have a vested interest in ensuring that defence policy and the allocation of national resources is geared in their favour.

A lack of scrutiny

The most recent parliamentary debate about space was less a ‘debate’ than an opportunity to ‘reaffirm the government’s commitment’ to the cause. The Minister for Creative Industries, Art and Tourism Chris Bryant was questioned by MPs, including the Scottish Lib Dems Alistair Carmicheal and Jamie Stone, and the Conservative’s Mark Garnier, who was the previous (and likely next) chair of the APPG for Space. Scotland has a leading role in the space industry with Europe’s leading satellite manufacturer based in Glasgow, and the nearly finished Saxavord Spaceport based in the Shetland Islands. Stone remarked that, ‘A space launch represents a social benefit to young people and jobs for the future in a fragile and remote part of the UK’, and Garnier said, ‘Everything the Minister has said so far is music to my ears’. The MPs simply sought greater clarification of strategy and intent to deepen the investment in space power. Regarding the spaceport in Shetland, Chris Bryant noted that commercial collaboration is ‘key to its success’ and said, ‘I am meeting with Airbus next week about it’.

Public conversations about SaxaVord rarely state its military intentions. Instead, the public are misled into believing its commercial prospects.

In a report by Drone Wars and CND entitled ‘For Heaven’s Sake: examining the UK’s Militarisation of Space’, the authors spoke to residents of Kodiak Island, which is home to the Pacific Spaceport Complex – Alaska (PSCA). One resident said: ‘We were promised many jobs. We were told that local residents would be trained to assemble satellites and that there would be all sorts of other jobs…there are less than fifteen jobs out there now.’ As most jobs at the SaxaVord port in Scotland will be highly skilled and specialist, it’s unlikely that large swathes of the local population will be qualified to work there.

Public conversations about SaxaVord rarely state its military intentions. Instead, the public are misled into believing its commercial prospects. Kodiak Island was promised to be the best location to launch commercial satellites, but according to one resident, ‘in the last 20 years the only launches that have taken place have been military or US government funded.’ The fuzzy commercial-military collaboration in space means that, ‘Although launches from the spaceports will be undertaken by commercial companies, it appears many of them will be used for military or dual use purposes.’

SaxaVord Spaceport on the island of Unst, the northernmost Shetland isle. Image: SaxaVord via Sky News

A repeated intention of the UK Space Command is to create ‘a sustainable space’, but rarely is there any meaningful explanation of how. Orbex, a company which is leading development in SaxaVord (taking over the contract previously held by Lockheed Martin) claims to be pioneering a ‘sustainable’ rocket fuel. According to the rocket scientist and peace activist David Webb, it is impossible to make rocket launches environmentally friendly: ‘Traditional chemical-based rocket fuels are used because a small volume/mass can provide a lot of energy. However, they leave particles of carbon and aluminium behind in the upper atmosphere, which damage the ozone layer and produce methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. More sustainable “green” fuels are being investigated; some use hydrogen and oxygen and electrolysis and others come from renewable carbon sources such as biomass. However, these still require a lot of energy to produce and maintain.’

Also, the SaxaVord port is located in an area of outstanding natural beauty with many protected species, which the heat blast radius around a launch site will destroy. The ‘For Heaven’s Sake’ report highlights more environmental, social and political threats from space militarisation and is a recommended next-step for further reading.

Same approach, different risks

Adopting the same narrative, employing the same people and giving contracts to the same companies will replicate the same destructive system that fuels conflict on Earth.

Space has no borders or territory to defend, and the security threats we face there cannot be treated in the same way as on earth. Adopting the same narrative, employing the same people and giving contracts to the same companies will replicate the same destructive system that fuels conflict on Earth. Greater investment in, and preparation for, war in space will increase the likelihood of it actually happening. It is a multifaceted and complex area that we must treat with extreme caution, rather than super-charging a new military era without any proper scrutiny or public consideration.

We can forecast that the new defence review will emphasise investment in the military space domain. This must be a catalyst for the media to critically monitor these developments rather than remain starry-eyed at the prospect of space adventures. Greater pressure must be placed on policy makers to establish boundaries with the commercial sector and develop international regulation before it’s too late.

This article was published during international Keep Space for Peace week (5th-12th October 2024). You can read about The Global Network here. In the UK, follow SpaceWatch for critical updates. Local campaigns include Pembrokeshire against DARC and Menwith Hill Accountability Campaign.

See more: military in society, Scotland, UK Parliament, Wales, arms industry, democracy, space

Like what you read?

> Sign up for our newsletter or blog notifications

> Support our work – from just £2 a month