Bodyguard gets it wrong

ForcesWatch comment

The recent BBC drama Bodyguard, featuring a ‘troubled veteran’ recently captivated on average 10.4 million viewers, reaching a peak of 11 million as it ended. It is the BBC’s most watched drama since 2008.

While there has been some important debate around Islamophobia and Bodyguard, given the way in which the series depicts a female hijab-wearing suicide bomber, there are also concerns about its portrayal of veterans, militarism and security.

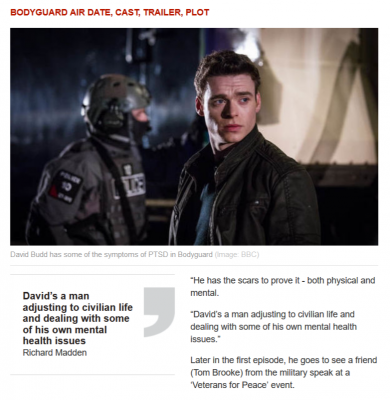

One of the media articles about Bodyguard that mis-named the fictional veterans group, calling it by the name of the real-life group Veterans for Peace.

The hero, David Budd, is a veteran. He is from the outset clearly disillusioned with the war on terror, suffers from PTSD and resents those who sent him and others to war. He now works for the police force. One of the earliest, most gripping scenes sees him trying to talk to a jihadi suicide bomber and persuade her not to detonate. He says to her:

‘You’ve been brainwashed. He has. [referring to her husband] You have. And I know. I was in Afghanistan. I saw mates get killed. Nearly got killed myself. For what? Nothing. Politicians. Cowards and liars. Ours and theirs. People full of talk but will never spill a drop of their own blood. But you and I, we’re just collateral damage.’

As a Principal Protection Officer for the London Metropolitan Police, David Budd is given the task of protecting the Home Secretary, Julia Montague. We see his internal conflict with this work, given his dislike for politicians like her who voted in favour of the war on terror and is pushing through tough new surveillances laws. However, he puts these feelings aside – despite the dismay of his similarly disillusioned friends from the ‘Veterans Peace Group’, and ends up having an affair with Julia Montague, mourning her death and fighting hard to find out who was responsible.

This places him in stark contrast with a nefarious veteran from the ‘Veterans Peace Group’, seen first speaking in one of their meetings where he says:

‘For decades, the West has been inflicting suffering on the poor and powerless. The war in the desert, in the oil fields, we’ve brought it back to the streets of Britain. There’s kids growing up over here, all they hear is what’s being done to family and friends over there. Who can blame them if they want to push back?’

This same veteran then turns out to be behind a terrorist attack on the Home Secretary’s life – he shoots at her car from a building, and kills several people. While the veterans motivation is rooted in his aversion to the war on terror which has – visibly – scarred him, and consequent loathing of the politicians who endorsed it; he is in fact recruited to kill her by shadowy figures from organised crime. His attempt fails, and he kills himself before being captured. Just before he kills himself, David Budd finds him – and the terrorist veteran attempts to pass the baton on, saying essentially that David must now be the one to kill the Home Secretary.

Both the police and frequently, the viewer, have suspicions about David as the series goes on – clearly struggling with his mental health and well placed to harm the Home Secretary. Is he at the heart of the series of terrorist attacks including the one that takes her life?

In the end however David is redeemed. He manages to piece together the whole picture and find both those responsible for killing the Home Secretary and the individual within the state security apparatus that is leaking information. He finally seeks help for his PTSD and a possible reconciliation with his estranged wife.

This whole narrative is a clumsy and inimical foray into the public imaginary with regards to veterans’ welfare including PTSD and moral injury, as well as conscientious objection, critical debate about war and security, and crucially, a very real veterans’ movement.

This veterans’ movement is Veterans for Peace, an organisation which was founded in the US after the Vietnam War. A UK group has been steadily growing since it started in the wake of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.. The motto of Veterans for Peace UK is ‘war is not the solution to the problems we face in the 21st century.’ Their members are all veterans of the armed forces who have fought in conflicts from WW2 to Afghanistan. They affirm: ‘We are not a pacifist organisation, we accept the inherent right of self-defence. We work toward increasing public awareness of the cost of war and to restrain our government from intervening in the internal affairs of other nations, for the larger purpose of world peace.’

They also mis-represented @VFPUK – disgraceful that they effectively copied our logo and name and made out that members are available as hired guns. We are completely non-violent – @BBC could have easily invented a #Veterans group with no copying our our logo etc.

— VFP UK (@vfpuk) September 26, 2018

The similarities between Veterans for Peace UK and the Bodyguard’s Veterans Peace Group are striking. From their name, to their mandate (the fictional Veterans Peace Group poster says ‘Bringing together veterans from the UK Armed Forces to provide support, education and campaign against conflict and intervention’) to their logo. The fictional logo is a helmet with a dove, the real logo is also a helmet with a dove, just with different colouring.

Many Veterans for Peace members have been, like David Budd and the Veterans Peace Group terrorist, injured physically, mentally and morally by their involvement in war. In articles talking about Bodyguard, the Veterans Peace Group has regularly been referred to as Veterans for Peace. Libel aside, they may as well have just used the actual name.

Veterans for Peace are not a story-line for the BBC to twist into something perverse and frightening. They are a leading part of the critical and honest debate we need to be having if we care about improving our global security.

Of course, the portrayal of a peaceful veterans’ group as a dangerous organisation whose members are terrorists or guns for hire, is insulting and slanderous. Their voice is vital and deserves respect; the expression and exploration of their perspectives should be welcomed, not misrepresented and set up as something to be feared.

Veterans have themselves witnessed the impact of the wars they fought in; they should never be defamed or vilified for daring to speak out against them. Nor should their redemption be found in working for and defending the same politicians who sent them to war.

David Budd’s journey, from anger towards the politicians who sent him to war, to their protector and hero, is rewarded with a trajectory towards greater wellbeing. Meanwhile the Veterans Peace Group terrorist acts out David’s alternative path – from disillusionment to resistance to violence, and ends up killing himself.

To present those veterans suffering from mental ill-health and moral injury or who have decided to oppose the war on terror as if they are potential terrorists, is insulting and immoral – and so far from reality.

The real Veterans for Peace can be seen marching peacefully on Remembrance Day, commemorating all those who have died in war with solemnity, respect and the words ‘Never Again.’ They can be seen speaking at peace events around the country, resisting militarism, and calling for Britain to become a neutral country that is prepared to defend its shores but not intervene in the security of another nation. They can be seen supporting calls for security to be considered in more sustainable and long-term ways, and arguing that the war on terror has been in many ways harmful.

Veterans for Peace lay a wreath of while poppies at the Cenotaph each year on Armastice Day.

Presenting Veterans for Peace as if its members are dangerously radicalised and may threaten our security, muddies the reflective debate about national and global security that we need to be having. Many would in fact argue that critical scrutiny of the morality of warfare; the rights of personnel, veterans and indeed the public to conscientiously object; and nonviolent resistance to militarism and war are actually critical to long-term sustainable security.

ForcesWatch is part of the Rethinking Security group – a coalition of pracitioners and academics who share a concern about the current approach to national security in the UK and beyond. Their National Coordinator, Celia McKeon, says:

‘As global security deteriorates, a critical debate about the impacts of UK foreign policy is increasingly important. It is in our interests, as a society, to grapple more honestly with the UK’s contributions to global insecurity, to challenge the flaws in the current approach, and to consider what other strategies and capabilities might be more effective.’

Veterans for Peace are not a story-line for the BBC to twist into something perverse and frightening. They are a leading part of the critical and honest debate we need to be having if we care about improving our global security.

See more: veterans, culture

Like what you read?

> Sign up for our newsletter or blog notifications

> Support our work – from just £2 a month