At particular risk: women and girls in the military

The Defence sub-committee on Women in the Armed Forces last week published a damning report on the situation for women in the armed forces. They concluded that, ‘Within the military culture of the Armed Forces and the MOD, it is still a man’s world.’ (p79)

The inquiry gathered a mass of evidence from many hundreds of women, with 1 in 10 serving women making a submission – itself an indication of the severity of the difficulties they experience. However, this is not a new area of concern. Likely embarrassed by external pressure, such as from Liberty’s Soldier’s Rights campaign (and now from the Centre for Military Justice and other women who have served), the Army first conducted a Sexual Harassment survey in 2015, followed by a review into ‘inappropriate behaviours’ and how they are dealt with in the Service Complaints System, both in 2019.

It is worth quoting the conclusions of the report at length:

There is too much bullying, harassment and discrimination – including criminal behaviours like sexual assault and rape – affecting Service personnel (both male and female), and the MOD’s own statistics leave no room for doubt that female Service personnel suffer disproportionately. We were alarmed and appalled that the Army’s Sexual Harassment survey of 2018 found that 21% of servicewomen had either experienced or witnessed sexual harassment at work in the previous 12 months. Such a figure should have raised major concerns in the Army but appears not to have done so. (p79)

The report notes MoD diversity initiatives and those to reduce unacceptable behaviour but makes the broad conclusion that, ‘it needs to be proactive in making more space for under-represented groups, including servicewomen, and reforming the prevailing culture.’

It condemns the attitude of many of those in the chain of command:

In particular, we are disturbed by repeated examples of senior ranks failing those they command, by not responding appropriately or even engaging in these behaviours themselves. Some of the language we heard from senior leaders also concerned us, as it appeared to imply servicewomen wanting to progress need to learn to put up with these behaviours. (p80)

They note that gap between policy and practice and the limiting context of the wider culture of the military, operating in a ‘unique environment’ where training ‘is often for combat and is intended to create a fighting force that is able to kill’.(p80) Nevertheless, they make a number of practical recommendations, including that the 2019 Wigston Review on inapprioriate behaviours is fully implemented, that female-specific uniforms and health facilities and services are developed and that flexible service is normalised. They also seek to address the significant gender imbalance amongst senior officers, noting that current MoD initiatives to address this is likely to be ineffective.

The report also states that the recommendations from the 2019 Lyons Review into the operation of the Service Complaints System be implemented. As the Service Complaints Ombudsman has pointed out in successive annual reports, women and minority ethnic personnel are significantly overrepresented in making complaints about bullying harassment and discrimination. Yet, the Women in Armed Forces report notes that the majority of those with a complaint do not take it to the Service Complaints Ombudsman because they do not think it will be property addressed and/or fear reprisals or the affect it will have on their career.

The report states that the chain of command are not ‘all properly equipped’ to handle complex cases and that ‘We even heard stories of senior ranks closing ranks and brushing complaints under the carpet rather than addressing them.’(p83)

As many have called for previously, the report recommends that rape and serious sexual assaults in the UK should be handled in the civilian justice system and taken out of the military justice system. Unfortunately, the Armed Forces Bill Committee only very recently failed to take the opportunity to write this important change into the new legislation. However, there is some hope that the Lords will now have the clear evidence needed to demand that this change be made.

No special consideration for girls in the armed forces

Much of our work centres around the experience of under 18s in the military. Our partner organisation Child Rights International Network submitted evidence relating to 16 and 17 year old girls whose risks of being in a military environment as a female are compounded by their young age. As CRIN states, these risk, ‘may be incompatible with the special protections afforded them in law’.

Each year around 200 girls join the armed forces with three quarters enlisting in the army. Ironically, it was the case of a 17 year old girl in the army who alleged she had been attacked by six soldiers that finally triggered the Wigston Review on inappropriate behaviours as well as a video response by the army’s Chief of General Staff promising that action would be taken.

Despite noting the military risk factors for sexual harassment and assault – including rank and age gradients and weak or absent controls – the Review did not discuss any special protections necessary for girls in the armed forces, who are still legally children. Unfortunately, the new Women in the Armed Forces report also did not make any specific recommendations in relation to this age group, although it notes evidence of the difficulties faced by young female recruits, including 60 incidents of abuse at the Army Foundation College in Harrogate where under 18s are trained, Given the additional barriers to making a complaint that a young recruit would face, this is a worrying oversight.

Army advertising – behind the curve

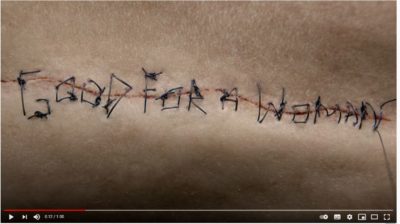

In the same week as the Women in Armed Forces report was published the army launched a new recruitment advert aimed at attracting female soldiers.

Declaring that ‘there is no such thing as the ladies team’ and depicting a quick succession of combat scenarios with female voice-overs spurning ‘beach body rations’ and ‘rifles for smaller hands’, the advert is intended to convey that enlisting is a ‘career defined by skill not gender’.

However, the advert seems to be sending a clear message that only women who agree to the current terms of military service (i.e. male orientated) need apply. Is this is riposte to the special considerations for women in the military that the report is asking for, including such basics as uniforms that fit properly, or just an ill-timed and overplayed nod to equality?

The Youtube blurb states that, ‘There are no ‘female soldiers’ in the British Army. Just soldiers. A soldier is a soldier. Equal pay. Equal opportunities. Equal expectations.’ This reveals a simplistic approach to equality, where all must compete on a level playing field despite the fact that the majority set the rules and have the most power. We feel it shows that the army has some way to go before it is recognising the demands of the Women in the Armed Forces report and the fundamental change needed to make them a reality.

See more: recruitment, recruitment age, risks, bullying and assault, military justice system

Like what you read?

> Sign up for our newsletter or blog notifications

> Support our work – from just £2 a month