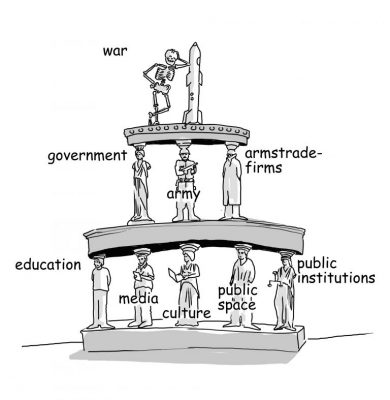

What is militarism?

Militarism is subject to many different definitions. This can make it hard to characterise for those seeking to expand their understanding of what is an important aspect of social culture.

Militarism, and the process of militarisation, is a broad and complex issue involving a diverse range of different groups and interests. While it has long been a central dynamic in British history, it has current manifestations that are particular to the present day.

ForcesWatch has found the following to be a useful starting definition of militarism:

- The normalisation of war and preparation for war.

- Prioritising the needs and interests of military institutions.

- Extension of military culture and influence into everyday life such as in education, central and local government and business, charities etc.

The following quote by Cynthia Enloe is also useful for thinking about how this is taken on and internalised by individuals:

“To become militarised is to adopt militaristic values and priorities as one’s own, to see military solutions as particularly effective, to see the world as a dangerous place best approached with militaristic attitudes.” (Globalization and Militarism: Feminists Make the Link, 2007)

In our view there is a substantial body of evidence that these aspects of militarism have become intensified over the last decade or more. This ‘new tide of militarisation’ can be traced through policy and practice and adds up to a concerted effort by government and the armed forces, and supported by others, to promote the military and to make sure that it has enough recruits to fight its battles and enough support to go to war.

One example of this effort was the report published by the Labour government on National Recognition of our Armed Forces in 2008, which stated that:

“Public understanding of the military and recognition of their role will always determine the climate within which the Forces can recruit, and the willingness of the taxpayer to finance them adequately.”

There have been many subsequent initiatives that have also worked to promote the interests of the military in wider society, including ‘military ethos’ (from 2012) and other military activities in schools, Armed Forces Day (from 2009) and other activities in public spaces, and the Armed Forces Community and Corporate Covenants (from 2013).

We have also seen how military interests are more represented in culture generally – in the media, in sport, at public events – and how military ceremonies such as Remembrance have been escalated in their level of public presence.

https://vimeo.com/276296290The 2018 feature documentary War School from POW Productions explores how a militarist message it sold to the public and young people in particular.

Auditing militarism

To understand if militarism is on the increase, we can look at how developments reflect the aspects of our definition outlined above.

To understand if militarism is on the increase, we can look at how developments reflect the aspects of our definition outlined above.

The advance of the military into education can be read as both an attempt to normalise the military within civil society and the result of the normalisation of military approaches. Our briefing on military influence in education and youth activities describes the many ways in which military interests (arms companies as well as the armed forces) are present within schools and colleges. This influence is not balanced by education for peace. Although there are many civil society initiatives around peace, human rights and social justice issues, this is not a fundamental part of the curriculum or much encouraged by the government. Thus the military as a key part of conflict resolution is not questioned and the sense of needing a strong military for the next war and supporting the arms industry holds sway.

The military is so normalised within society that criticism of its activities in general are seen as marginal, although some particular military actions do gain more public critique. Alternative policy approaches to security are also marginalised. Thus many schools embrace military activities and institutions as depoliticised and uncontroversial and do not question the defence agendas privileged and played out within education. Those that resist this are characterised as marginal and as politicising the debate.

Everyday militarism poster by Quakers in Britain

Part of this normalising process involves portraying the military as having the (unique) capability of providing solutions to complex social problems. Again, this has particularly happened within education. which has long been subject to being characterised as in crisis and political interference by successive governments.

We have seen the Department for Education promoting ‘military ethos’ in schools via cadet forces and Troops to Teachers and military-themed alternative provision for troubled young people. Statements are made about the unique qualities and values of the military to create a sense of service, resilience, leadership etc, implicitly making the assumption that serving and ex-military personal are more able to do this than those working in other public services.

These programmes are explicitly targeted towards disadvantaged communities and government commissioned ‘evaluations’ of them have made exaggerated claims about their impact on those young people who are seen to be ‘failing’ what is expected og them.

As a result of wide acceptance of this narrative, there has been little questioning of whether it is appropriate for defence agendas to be promoted within education and if they operate in the best interests of young people. Public debate has been limited and formal scrutiny almost zero, with the exception of debates in the Scottish and Welsh parliaments.

While the extension of military culture is perhaps most focused towards potential recruits and ‘future opinion formers’ in schools and youth activities, there is a wider increase in military influence into everyday life. We can all sense that this is happening but it is important to understand the mechanisms through which this has developed.

One mechanism that warrants more attention than it receives is the Armed Forces Community Covenant and its partner, the Armed Forces Corporate Covenant. These initiatives involve public, private and charitable bodies pledging support for the armed forces. This extends beyond the reasonable concept of ‘removing disadvantage’ in access to services for serving personnel and veterans, to one of generating public support for the institutions of the military.

This amounts to the interests of the armed forces becoming embedded into civilian institutions and those institutions working to further those interests. For example, we are seeing how these pledges are committing local authorities to putting on lavish Armed Forces Day events and to facilitating other public recruiting displays. Employees and the public are encouraged to ‘salute our forces’ around Armed Forces Day in addition to various other ways in which individuals are asked to make a public display of gratitude to the military, thus adopting its interests as their own.

Resources

You can read more about ‘the new tide of militarisation’ in the following articles and publications from ForcesWatch and others. We hope this will provide a good starting point for understanding contemporary militarism in the UK.

Warrior Nation: war, militarisation and British democracy

In 2018 ForcesWatch pu blished a report by Professor Paul Dixon of Birkbeck University. The report covers a range of issues including the ‘militarisation offensive’ of the last decade, the changing relationship of the military to democracy and the importance of public opinion for expeditionary warfare. It can be read and downloaded here.

blished a report by Professor Paul Dixon of Birkbeck University. The report covers a range of issues including the ‘militarisation offensive’ of the last decade, the changing relationship of the military to democracy and the importance of public opinion for expeditionary warfare. It can be read and downloaded here.

Three films of presentations on aspects of militarism and a summary of the report themes are also available.

Take Action on Militarism: A resource pack and website

In 2017 ForcesWatch and the Quakers recognised that there was a need for a resource which could be used at grassroots level to challenge militarism in local communities.

The Take Action on Militarism pack provides background information about issues such as military influence in education, critical perspectives on Remembrance and the relationship of the arms industry to militarism.

The pack can be downloaded from the Take Action on Militarism website and hard copies are available to order.

Spectacle, Reality, Resistance: Confronting a culture of militarism

If you would like a longer exploration of militarism in the UK context, this book by David Gee published by, and available from, ForcesWatch looks at the culture of militarism in Britain.

It explores its dynamics – distance, romance, control – in three essays, accompanied by three shorter pieces about the cultural treatment of war and resistance to the government’s increasingly prodigious efforts to regain control of the narrative. See more and buy the book

The New Tide of Militarisation

This briefing from the Quakers (updated in 2018) explores the government strategy to increase public support for the military, and the concerns this raises.

Articles

The creep of militarism into our civil institutions

This article looks at attempts to institutionalise public support for the military as the battle for control of the First World War centenary narrative started in 2014.

Armed Forces Day and other ways of manufacturing consent

While it is a very new invention Armed Forces Day has become a centrepiece of the militarist calendar. This 2015 article looks at the rise of this annual event and how it fits into the new wave of militarism.

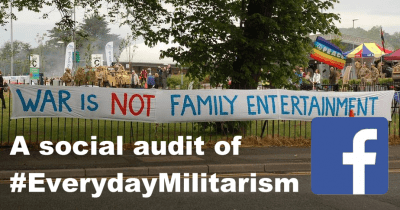

Militarism The Whole family Can Enjoy

This 2017 article explores aspects of local authorities organisation of Armed Forces Day events such as the often signifcant financial cost and sponsorship by arms companies.

Films

See more: military in society,

Like what you read?

> Sign up for our newsletter or blog notifications

> Support our work – from just £2 a month